TRIGGER WARNING: GRAPHIC DESCRIPTIONS OF VIOLENCE, DEATH, INJURIES AND MAYHEM.

On April 25, the commandant Yakovlev arrived at the Governor's Mansion with the intention of taking the Imperial family to another location. He told Nicholas that he had orders to take him away, but he did not say why or where to. He refused to leave, but Yakovlev warned him that if he continued to resist, he would have to be taken away by force. It was believed that Nicholas was to be taken to Moscow to be put on trial and to a terrifyingly unknown fate. Alexandra did not want him to go without her, and her anxiety was indescribably overwhelming as she faced the most agonising choice of her life.

"After lunch, Commissioner Yakovlev came, because I wanted to organize a visit to the church during Holy Week. Instead, he announced the order of his government (the Bolsheviks) that he should take us away (where?). Seeing that Baby was very sick, he wanted to take Nicky alone (if not willing, then obliged to use force).

I had to decide whether to stay with ill Baby or accompany him [Nicky]. Settled to accompany him, as can be of more need and too risky not to know where and for what (we imagined Moscow). Horrible suffering. Maria comes with us. Olga will look after Baby, Tatiana — the household, and Anastasia will cheer all up. We take Valya, Niuta, and Evgeny Sergeyevich Botkin offered to go with us." - Alexandra's diary entry, written April 25, 1918 — clearly in a state of emotional exhaustion.

Sophie Buxhoeveden and Pierre Gilliard went into more detail about it:

"This was the most terrible time of all for the Empress. She was torn between her feelings as a wife and as a mother. She felt that she could not allow the Emperor to go alone. On the other hand, her boy lay dangerously ill, and the idea of leaving him in that state drove her nearly out of her senses. It was the only time that she completely lost her self-command, pacing up and down the room for hours in her perplexity. The Emperor's departure was imminent and some decision had to be taken.

At last the Grand Duchess Tatiana forced her mother to come to a decision. 'You cannot go on tormenting yourself like this,' she said. The Empress summoned all her courage, and went to the Emperor to tell him that she had made up her mind to go with him. The Tsarevich could be looked after by his sisters, and she felt she must be with the Emperor. The girls settled amongst themselves that the Grand Duchess Marie, who was the strongest, physically, of the sisters, should go with their parents. Olga Nicholaevna was to take charge of the house, Tatiana Nicholaevna was to look after her brother, Anastasia Nicholaevna was too young to be taken into account. Prince Dolgorukov had asked the Emperor which of the gentlemen should go with him, and the Emperor had chosen him. Dr. Botkin also appeared, carrying his well-known small black bag, and when he was asked why he had brought it, said that as he was, naturally, going with his patient (meaning the Empress), he might need it. The Imperial Family spent the rest of that day alone. The sick boy had to be prepared for his parents' leaving, and the Empress spent most of the time with him, trying to treat her departure in a casual way so as not to frighten him, and telling him that he and his sisters would soon follow her." - from The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna (1928), written by Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden

"Thursday, April 25th - Shortly before three o'clock, as I was going along the passage, I met two servants sobbing. They told me that Yakovlev has come to tell the Tsar that he is taking him away. What can be happening? I dare not go up without being summoned, and went back to my room. Almost immediately, Tatiana Nicolaievna knocked at my door. She was in tears, and told me Her Majesty was asking for me. I followed her. The Tsarina was alone, greatly upset. She confirmed what I had heard, that Yakovlev has been sent from Moscow to take the Tsar away and is to leave tonight.

'The commissary says that no harm will come to the Tsar, and that if anyone wishes to accompany him there will be no objection. I can't let the Tsar go alone. They want to separate him from his family as they did before (the Tsarina was alluding to the Tsar's abdication)...'

'They're going to try to force his hand by making him anxious about his family... The Tsar is necessary to them; they feel that he alone represents Russia... Together we shall be in a better position to resist them, and I ought to be at his side in the time of trial... But the boy is still so ill... Suppose some complication sets in... Oh, God, what ghastly torture!... For the first time in my life I don't know what I ought to do; I've always felt inspired whenever I've had to take a decision, and now I can't think...'

'But God won't allow the Tsar's departure; it can't, it must not be, I'm sure the thaw will begin tonight (When the thaw set in the river was impassable for several days; it was time before the ferry could be re-started)...'

Tatiana Nicolaievna here intervened:

'But mother, if father has to go, whatever we say, something must be decided...'

I took up the cudgels on Tatiana Nicolaievna's behalf, remarking that Aleksey Nicolaievich was better, and that we should take great care of him.

Her Majesty was obviously tortured by indecision; she paced up and down the room, and went on talking, rather to herself than to us. At last she came up to me and said:

'Yes, that will be best; I'll go with the Tsar; I shall trust Aleksey to you...'

A moment later the Tsar came in. The Tsarina walked towards him, saying:

'It's settled; I'll go with you, and Marie will come too.'

The Tsar replied: 'Very well, if you wish it.'" - from Thirteen Years at the Russian Court (1921), written by Pierre Gilliard

"In the evening the Household joined the Imperial Family at tea. The Grand Duchesses all sat as close to their mother as they could, looking the picture of despair." - from The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna (1928), written by Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden

"This evening at half-past ten we went up to take tea. The Tsarina was seated on the divan with two of her daughters beside her. Their faces were swollen with crying. We all did our best to bide our grief and to maintain outward calm. We felt that for one to give way would cause all to break down. The Tsar and Tsarina were calm and collected. It is apparent that they are prepared for any sacrifices, even of their lives, if God in his inscrutable wisdom should require it for the country's welfare. They have never shown greater kindness or solicitude.

This splendid serenity of theirs, this wonderful faith, proved infectious.

At half-past eleven the servants were assembled in the large hall. Their Majesties and Marie Nicolaievna took leave of them. The Tsar embraced every man, the Tsarina every woman. Almost all were in tears. Their Majesties withdrew; we all went down to my room." - from Thirteen Years at the Russian Court (1921), written by Pierre Gilliard

At about 3 a.m. the next morning, Nicholas, Alexandra and Maria left Tobolsk.

Above: The last known photo of Nicholas and Alexandra.

Above: The carts outside the house at Tobolsk.

"About four some springless carts were drawn up before the main entrance. The one destined for the Empress had a hood, and into this she was lifted; Dr. Botkin said that it was impossible that she should travel in such discomfort — the carts had no seats — so some straw was brought from a pigsty to put at the bottom of the cart, over which some rugs and pillows were arranged. The Empress motioned to the Emperor to follow her, but Yakovlev said that he had to travel with him, and the Grand Duchess Marie got in beside her mother. ... the whole convoy drove off at four a.m. at full speed, clattering over the streets in the dim, morning light. The three Grand Duchesses stood looking after them, and it was a long time before their lonely figures disappeared behind the open door. The journey was terrible, and it can be imagined what the Empress suffered when she was rattled at full speed over the awful Siberian roads. These roads are shocking at the best of times, and just then were at their worst, for the snow and ice melted during the daytime, and froze again into hard lumps at night. The Empress sent me a line from Tyumen, saying that all her 'soul had been shaken out.' Several times wheels came off and broke, and the harness gave way.

They travelled all day, spending some hours at night fit in a peasant's house! where they slept on the camp-beds they had brought with them, the Emperor and Empress with their daughter in one room, the gentlemen in another. The ladies were nearly frozen. Someone who saw them at one of their stops said that when the Grand Duchess got out to arrange her mother's cushions, her hands were so cold that she had to rub her numbed fingers for a long time before she could use them at all. She and the Empress wore thin coats of Persian lamb suitable for motor-car driving in Petrograd. They had to get over several rivers, where the ice was so unsafe that they were obliged to cross by planks on foot. At one place the Emperor had to wade knee-deep in ice-cold water, carrying the Empress in his arms. The state in which they reached Tyumen can be imagined, yet the Empress begged Yakovlev to send an encouraging telegram to her children, saying that they had 'arrived all well.'" - from The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna (1928), written by Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden

"The beginning of the trip was unpleasant and depressing; it was better after we got into the train. It's not clear how things will be there." - except from Alexandra's letter to Olga, written April 18 (O.S.), 1918

"At Tyumen a train was awaiting them. It seems likely that it was Yakovlev's original intention to take them to Moscow. There are two ways of reaching that city from Tyumen. The one westward, through Ekaterinburg, the other by going first eastward to Omsk, branching off from there via Cheliabinsk. Yakovlev chose the latter to avoid Ekaterinburg, where there was an ultra-Red Soviet. They reached the station before Omsk safely, but the authorities at Omsk were evidently afraid that the prisoners might escape further east and would not allow them to be taken beyond their town. Yakovlev had many discussions with the Omsk Soviet, and spoke direct to Moscow. As a result of the instructions he got, the train was turned back towards Ekaterinburg, which had evidently been warned of their arrival. When the train stopped outside the town, a large band of soldiers surrounded it. Yakovlev went to the local Soviet, and there, apparently, resigned his powers, and the Emperor and Empress were handed over to the Ural (Ekaterinburg) authorities. The Emperor, Empress and their daughter, with Dr. Botkin, the maid and the two men-servants were taken in motor cars to the house of a local engineer named Ipatiev where they were imprisoned. Prince Dolgorukov was taken to the prison in the town (April 30th).

The Empress was utterly weary in body and spirit. She was hardly able to stand when she left the car. She had no news of Alexei Nicholaevich. The letters she had written daily to her children had no answer, and she was desperately anxious. Happily a telegram soon came from the Grand Duchess Olga Nicholaevna describing an improvement in the boy's health, but she never got most of the letters the children wrote her. Still she seems at first to have had hopes that the stay at Ekaterinburg would not be a long one, and her chief trouble seems to have been her children's absence and the idea of their journey." - from The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna (1928), written by Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden

"We came here by railway on motors. Had breakfast from a common food supply at 4:30. Unpacked only in the evening because all things were examined, even the medicine and the 'lollipops'. ... We drank tea together at 9:30 then still sat on own beds and went to bed at 11:00." - excerpt from Nicholas's, Alexandra's and Maria's letter from Ekaterinburg to Olga, Tatiana, Anastasia and Alexei in Tobolsk, written April 18, 1918

Nicholas, Alexandra, Maria and the servants had arrived at the Ipatiev House — which was ominously also called "The House of Special Purpose". It was here that their treatment would become worse than it ever had been before, and their already restricted freedoms became even more so.

"The house at Ekaterinburg was much smaller than that in Tobolsk. It had belonged to a well-to-do engineer named Ipatiev, and had been requisitioned by the Soviet. Two days before the Imperial Family arrived, I was told it had been hastily got more or less into order, and a high wooden paling was put up all round it, so that only the upper panes of the windows could be seen from the street. The party had the use of three rooms: a bedroom, which was occupied by the Emperor, Empress and their daughter; a sitting-room, where Dr. Botkin and the men-servants slept at night; and a room, meant for the Emperor's dressing-room, in which the maid, Anna Demidova, slept on a camp-bed. The remainder of the house was occupied by the Kommissars and the guard. The furniture had belonged to the former owners. The Imperial Family could not realise at all where they were staying, as nothing could be seen from the windows except the gilt cross on top of the belfry of a church in the square opposite. There was a small garden belonging to the house, which, later, they were allowed to use at stated hours. They could not go freely in and out as they had done at Tobolsk. All the things they had brought with them were thoroughly searched. The men even wrenched the Empress's grey suede hand-bag rudely out of her hands, though she had only her heart-drops, pocket handkerchief and smelling-salts inside it. This was the only time that the Emperor showed acute irritation. The rudeness to his wife thoroughly roused him, and he said sharply to the Kommissar, that, up till now, they had at least been treated with common civility. The man retorted rudely that thy were the masters now and could do as they pleased, and was so aggressive that the Empress had to pacify the Emperor for fear of causing trouble. From that time the valet Chemodourov told me the Kommissars were always rude to them. Their Majesties' dinner was brought in to them from a Soviet restaurant. It was coarse food, and the Empress could scarcely touch it. It was brought at most irregular hours, when it occurred to the guard, and was sometimes delayed till three or four PM. They often had no tea for breakfast, as the soldiers used up all the hot water. Supper consisted of the remains of the midday meal, warmed up by the maid. The servants had to sit at table with the Imperial Family, by order of the Kommissar. At first they refused to do this, out of respect for their masters, and agreed only at the Emperor's express command. There were neither tablecloths nor napkins, and only five forks for seven people. Dr. Botkin pleaded unsuccessfully for better food and for some comforts for the Empress, but his appeals were unheeded. Not only did the Kommissar and the guard help themselves to the dishes before they ever reached the Imperial table, but often one of them would come in during the meal and, pushing aside the Emperor, would pick some piece he fancied out of the dish with his fork, saying that by now they had had enough! The Imperial Family had to be up and dressed by 8:15 A.M., when the new Kommissar came to 'inspect.' He was a drunken workman called Avdeev, from one of the factories near the town. He was rude and totally wanting in any consideration. The eight riflemen who had come with Iakovlev's men from Tobolsk were imprisoned for several days in the basement of the Ipatiev house, and then sent back with their officer Matveev to Tobolsk. The men now on guard were men from the Syssert and Zlokazov factories. The men forming the outer guard were often changed. The inner guard had been specially chosen from among the most militant Bolsheviks, and they spared the Emperor and Empress no vexation or unpleasantness. The doors between the rooms had been taken off their hinges, so that they might see all the rooms at one glance when they came in. They would appear at any moment, without warning. A sentry was posted at the door of the lavatory and followed the Empress and her daughter at every step. Their remarks were rude and disgusting, and Dr. Botkin's complaints to the Kommissar were ignored.

The little money they had brought with them was taken away, so that they could not get anything they needed. The only red-letter days for the Empress were the rare ones on which she got a small note from her children at Tobolsk. Holy Week came, but no church was allowed. They asked to be given fasting food, but could only get a little gruel for the Empress. On Maundy Thursday they put all their ikons on a table in the sitting-room, and at vesper-time the Emperor and Dr. Botkin read the Gospel for the day. Even now the Empress does not seem quite to have abandoned hope that, when the children joined them, they would be moved somewhere else and that things would improve." - from The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna (1928), written by Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden

Above: The Ipatiev House. It eventually became a pilgrimage site and was demolished in 1977.

Above: Nicholas' and Alexandra's bedroom in the Ipatiev House.

The three described and gave warnings about what to expect from the conditions at the Ipatiev House to the rest of the children back in Tobolsk. The sympathetic guards there were also replaced with stricter and crueler ones, and in addition to sorely missing their parents and sister, the children were full of anxiety, especially the deeply sensitive Olga. After a month, Alexei had recovered enough that in May they were taken onboard the Rus to join the rest of the family in Ekaterinburg, where they reunited on May 23. Although most of their belongings were confiscated upon arrival, the family was happy just to be together again. The long month without seeing each other must have felt like a torturous eternity.

In the meantime, Alexei, who was now deprived of his tutors and faithful "sailor nanny" Nagorny (who had been arrested and the latter murdered; the other sailor nanny, Derevenko, had betrayed the boy), was in low spirits, and his recovery from his latest hemophilia attack was slow. His knee was swollen with bleeding, and as the blood began the gradual process of seeping back into his body, his symptoms worsened, and his temperature rose; and the narcotic he was administered did little to relieve his pain. As always, Alexandra kept vigil at his bedside.

"Baby slept on the whole well, though woke up every hour — pains less strong." - from Alexandra's diary, written May 28, 1918

"Baby's night was better." - from Alexandra's diary, written May 29

The other doctor, Derevenko (no relation to the renegade sailor), put Alexei's leg into a splint with a casing of plaster of Paris so as to straighten the leg and hasten the reabsorption process, but recovery remained slow, which was agonising for both the boy and his exhausted mother; and it was twelve long days before Dr. Derevenko pronounced him cured. This deeply unpleasant treatment of wrapping and immobilising Alexei's limbs in casts and splints was routine whenever he bled into his joints. It was just as unpleasant for Alexandra to have to witness, knowing that she had given him his disease from her side of the family.

June 6th, 1918 came and went — Alexandra's 46th birthday. Starting at around that same time, yet another new set of guards was installed, led by Yakov Yurovsky, and with them came not just more rules, restrictions and cruelty, but a deep sense of terror. Nicholas even admitted in his diary that when introduced to Yurovsky, he did not like him at all and felt genuinely fearful of him. The Romanovs already couldn't even look out the windows, which had been covered with newspapers before being coated in white paint, but now they couldn't look out the windows in the sense that they weren't allowed to because Yurovsky had ordered that anyone caught even just going too close to a window would be shot. An iron grille was built in after Alexandra ignored the order. They had to ring a bell every time they had to use the bathroom, and the guards even followed the four daughters to the lavatory. The family's rooms were right next to the room where the guards would drunkenly play piano and sing songs glorifying the revolution, and Alexandra and her family would try to drown them out by singing hymns. The guards etched revolutionary slogans and crudely drawn pornographic cartoons of Alexandra and Rasputin on the bathroom walls, and, often drunk, they would even say swear words and make dirty jokes in the presence of Alexandra and her daughters. The family also stopped receiving newspapers, and they were now forbidden to send or receive letters. Food sent to them as gifts from local nuns were stolen by the guards, and when Princess Helene of Serbia tried to gain entry to the house so she could visit the Romanovs, she was turned away at gunpoint.

Alexandra's routine in captivity and in the Ipatiev House: She only occasionally went into the garden and preferred to stay inside the house. To make sure she wouldn't feel lonely, one of her daughters would stay at her side, reading aloud to her while the others walked outside. Every time Alexandra didn't go out for a walk, it meant one of her daughters missed out on exercise, so the sisters organised things so that they would spend time with their mother in shifts, with one assigned to her in the morning and another in the afternoon. When Alexandra did go outside, it was usually just to sit on the steps of the main entrance. Until the sending and receiving of letters were forbidden, Alexandra spent the evenings reading or writing letters to her friends, as was seen in the previous part. All the family's correspondence was subject to censorship, and only some of the letters reached their intended recipients. Although soup and meat cutlets were always for lunch and dinner, Alexandra only ate macaroni prepared specially for her, as she had done for years as part of a special diet that her doctors had put her on.

In the weeks of June and early July 1918, although the Romanovs had no idea of what it would be, they all seemed to sense that something was going to happen to them. They had not been allowed to have a church service since May 24, but on July 14, a Sunday, they were allowed one. The priest conducting the service was Father Ivan Storozhev. He noticed that there was a great change in the whole family's demeanour since the last time he'd seen them on June 1. They seemed depressed and withdrawn — the girls didn't sing the responses during the liturgy. At a determined moment, the deacon began to recite the prayer for the dead, but he sang it instead of read it. At that moment, Alexandra and her family suddenly all audibly fell to their knees, seemingly out of despair. At the end of the service, which was surely an indescribable consolation to them, they all lined up to kiss the Cross and for Nicholas and Alexandra to take Holy Communion, and one of the girls whispered a tearful "Thank you" to Father Storozhev. He and the deacon left with the disturbing impression that something had happened to the family because of their sudden low spirits.

"Grey morning, later lovely sunshine. Baby has a slight cold. All went out ½ hour in the morning, Olga & I arranged our medicines. Tatiana read Spiritual reading. They went out, Tatiana stayed with me & we read Book of prophet Amos and prophet Audios. Tatted. Every morning the Komendant comes to our rooms, at last after a week brought eggs again for Baby.

8 Supper.

Suddenly, Lenka Sednev was fetched to go & see his Uncle & flew off — wonder whether it's true & we shall see the boy back again!

Played bezique with Nicky.

10½ to bed. 15 degrees." - Alexandra's diary entry, written on the night of Tuesday, July 16, 1918

These were the last words Alexandra ever wrote. In an ironic twist of fate, she had already written July 17th to date the next diary entry, one that ultimately would never be written.

At around midnight on July 17, 1918, the family were woken up and told that a Czech army was entering the town, shooting in the streets was to be expected, and they were to be moved to yet another new location for their safety, so they had to get dressed and come downstairs. They were also told that they were to have their photo taken so as to disprove rumours of their deaths. After they were all dressed, they were taken downstairs, across the courtyard, and into a cellar room, with Dr. Botkin, Alexandra's maid Anna Demidova, the cook, Ivan Kharitonov, and a valet, Alexis Trupp. Alexandra requested chairs to be brought in for herself and Alexei, and Yurovsky arranged everyone in preparation for being photographed. The eleven were left alone in the cellar for about 30 minutes. Although they were under strict orders to speak only in Russian, Alexandra whispered something to her daughters in English.

After the 30 minutes of waiting, Yurovsky came in and ordered the prisoners to stand up. Alexandra pulled herself up, "with a flash of anger in her eyes". Yurovsky had a piece of paper in hand. He read it aloud. It was a decree from the Ural Soviet Committee that ordered that Nicholas and his family had been sentenced to death and were to be shot, and ten gunmen entered the room; they and Yurovsky were armed with pistols. A horrified Nicholas shouted: "Lord, oh, my God! Oh, my God! What is this?!"

After his horror turned to shock and disbelief, Nicholas said, "I can't understand you. Read it again, please." An irritated Yurovsky read the decree a second time, and now it all began to sink in. Alexandra and her daughters made the sign of the Cross. Nicholas, stunned, merely responded with, "What? What?!". Yurovsky whipped out his pistol and pulled the trigger with "This!" in response. A numb but horrified Alexandra was forced to watch as the love of her life was gunned down right in front of her, all the gunmen shooting him at once. The four girls began to scream at the sight of their father's horrible death and in terror of the knowledge that they were next, and then the gunmen turned on Alexandra, her daughters, her son, and their servants as the shooting became "increasingly disorderly" and the bullets ricocheted around the room.

It is said that during the first round of gunfire, and despite having watched her husband of 23 years be killed in front of her, the deeply religious Alexandra did not panic and instead instinctively and almost on reflex tried to make the sign of the Cross in order to comfort herself, but ultimately was unable to finish the gesture when she was shot down. Eyewitness accounts and analysis of her skull have revealed a more exact picture of how she died. One of the executioners, Peter Ermakov, who was drunk and raging at the time, turned his attention to Alexandra, who was standing six feet away from him. Just as he raised his gun and aimed it at her, she turned her head away and made the sign of the Cross again. But before she could finish, Ermakov pulled the trigger. The bullet entered the left side of Alexandra's head and exited through her right ear as the force jolted her back and knocked her to the floor. She died on impact.

It took 20 horrific minutes to kill everyone. The room was a terrible mess of gunsmoke, bullet holes in the walls, and covered with blood, brain matter and other bodily fluids. In his drunken frenzy, Ermakov began to stab Nicholas and Alexandra with his bayonet, stabbing the dead Empress in the stomach and chest. The blade went so deep that it chipped off a piece of Alexandra's spine and cracked her ribs. When it was all over, the bodies were loaded onto stretchers and loaded into the bed of the waiting Fiat truck — during which time Maria and Anastasia were found to be still alive and quickly but horribly killed — and off they went.

They were taken into the Koptyaki Forest, just outside the town. There, the bodies were stripped and searched, where it was found that Alexandra and her daughters had been wearing jewels that they had sewn into their corsets and bras, which had acted as unintended makeshift bulletproof vests during the shooting. Medicines was the codeword that they used for these jewels. On Alexandra's waist was found a few long strands of pearls wrapped in silk and there was a large, thin strand of gold wrapped in a coil and hidden beneath her clothes. Around her neck was an amulet containing a miniature portrait of Rasputin and the text of a prayer, which her daughters were also wearing. During the strip-search, Alexandra suffered yet another indignity in death: one of the men fondled her, and he even bragged that he could die happy for having done it.

The eleven corpses had their faces smashed in with rifle butts and then doused in sulphuric acid to disfigure them beyond recognition, and they were dumped into the black water at the bottom of the Ganina Yama pit in the abandoned Four Brothers mineshaft; grenades were thrown in after them to explode and collapse the walls, as the "grave" was too shallow. The blood-soaked clothes were burned. Early the next morning, at dawn, the frozen and naked bodies were exhumed and reburied at the Porosenkov Ravine, deeper into the forest and four and a half miles from Ganina Yama, but the bodies of Maria and Alexei were dismembered and subjected to a botched cremation before being buried in a spot a few miles away from where the other nine bodies were buried.

Initial reports claimed that only Nicholas had been killed, others that Alexei had also been killed, and that Alexandra and her daughters were either still alive somewhere or had been killed later on, but eventually the Soviets came out with the truth and revealed that the entire family had been killed.

Alexandra's sister Ella was thrown down a mineshaft alive and murdered by the Bolsheviks on July 18, 1918, and her brother Ernst, who had always feared dying alone, died with his children and grandchildren in a plane crash in 1937, excepting his daughter Elisabeth, who had died years earlier from typhoid fever in 1903 at the age of eight. Alexandra's mother-in-law, Marie Feodorovna fled Russia with her daughters Olga and Xenia in 1919; and she lived in her native Denmark until her own death in 1928, outliving Nicholas, Alexandra and their children by ten years. Until her dying day, she literally refused to believe that Nicholas and his family had been killed, and out of desperation after a lifetime of losses, she convinced herself that they were living in exile somewhere.

Above: Ella.

Above: Ernst as an old man with his son and grandson.

Above: Ernst's daughter from his first marriage and Alexandra's niece, Elisabeth, who died in 1903.

Above: Marie Feodorovna in exile during the last years of her life, having outlived all of her sons as well as her daughter-in-law and five of her grandchildren.

In 1991, after 74 years in power, the mighty Soviet Union collapsed, and decades of state secrets and government cover-ups were waiting to be revealed and exposed. In July of that year, archeologists ventured into the Koptyaki Forest and dug nine skeletons out of the mass grave that they had lain in for 73 years. The gravesite had previously been discovered in 1979 by amateur geologist Geli Ryabov, but he vowed to keep his discovery a secret until political conditions in Russia were safe enough to reveal it. The bodies were taken to the Ekaterinburg morgue. DNA testing and facial recognition software confirmed beyond any scientific doubt that these were the remains of the Romanovs. Alexandra's identity was matched to that of skeleton number 7, which was that of a woman in middle age at the time of death.

On July 17, 1998, 80 years to the day after their deaths, the remains of Nicholas, Alexandra, and three of their daughters were laid to rest among their ancestors in the St. Peter and Paul Cathedral, the Romanov family tomb. The fragmented and burned bones of Maria and Alexei were not found until 2007, and they unfortunately have yet to be buried due to the Russian Orthodox Church's doubts over the authenticity of the remains.

Above: Forensic reconstruction of Alexandra's face, made by S.A. Nikitin in 1994.

Above The Romanov family tomb in the St. Peter and Paul Cathedral. Photo courtesy of Dennis Jarvis via Wikimedia Commons.

Above: A pearl earring belonging to Alexandra which was found near the mass grave.

Above: A brilliant belonging to Alexandra, found near the bonfire site by a birch tree, and a charred emerald cross also belonging to her that was found at the bonfire site by the shaft.

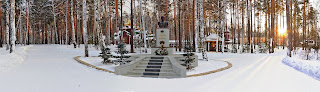

Above: A monastery built in the area around Ganina Yama. Photo courtesy of Sergei Martsynyuk via Wikimedia Commons.

Above: A chapel built on the Ganina Yama site. Photo courtesy of Hardscarf on Wikimedia Commons.

Above: The Church upon the Blood, built between 2000 and 2003 over the site where the Ipatiev House once stood. Photo courtesy of amanderson2 via Wikimedia Commons.

Above: A memorial altar to the Romanovs in the Church upon the Blood. The altar room is on the site where the cellar room in which they were killed once was.

In 2000, along with the rest of her family, Alexandra was canonised as a passion bearer saint in the Russian Orthodox Church. The R.O.C. outside Russia had canonised them as New Martyrs in 1981. In Eastern Christianity, passion bearers are people who face their death in a Christ-like manner; unlike martyrs, passion bearers are not killed for their faith, but they maintain it with deep piety and love of God, and they keep their dignity despite being subjected to humiliation. Since the canonisation, Orthodox faithful have attributed miracles such as intervention in stressful life events and healing from incurable illnesses to the prayers of Alexandra and her family.

A few months before her death, Alexandra wrote this prayer:

"O Lord, send us patience

During these dark, tumultuous days

To stand the people's persecution

And the tortures of our executioners.

Give us strength, O God so righteous

To forgive our neighbor's wickedness

And to greet the bloody, heavy cross

With Your meekness.

In these days of mutinous unrest

When our enemies rob us,

Christ the Savior, help us

Bear insult and disgrace.

Lord of the world, God of the universe,

Bless us with prayer

And grant peace to the humble soul

In this unbearable and fearful hour.

And at the threshold of the grave

Breathe a power that is beyond man

Into the lips of Your slaves

To pray meekly for their enemies." - prayer written by Alexandra on January 11, 1918

Above: The Holy Royal Martyr Empress Alexandra Feodorovna.

No comments:

Post a Comment