Source:

The Czarina in

The Queens of Europe by Margaret Sherrington in

The Canadian Magazine, issue of August 1902

http://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06251_114/66?r=0&s=1

This article on Alexandra was written as part of the series

The Queens of Europe by Margaret Sherrington for the August 1902 issue of

The Canadian Magazine.

The article:

IT is a big step from the position of a girlish Princess, of comparatively humble means, and brought up in an essentially quiet, domesticated household in Darmstadt, to that of Empress of Russia, with its heavy responsibilities, dazzling brilliance, wealth, and perils, and it is small wonder that Princess Alix of Hesse hesitated before accepting the suit that, if favoured, would necessarily bring with it the harassing life that is inseparable from the exalted position of a Czarina.

Although Nicholas II was only heir-apparent when he wooed Princess Alix, it was an Emperor, not a Czarewitch, that she wedded, his accession taking place a few months after his engagement.

The Czarina is the youngest child of the late Grand Duke and Grand Duchess of Hesse, the Duchess being, of course, the ever-lamented Princess Alice of England, whose beautiful character the Czarina inherits in a marked degree.

Perhaps no Princess in modern history has known the pinch of poverty so well as did Princess Alice, whose pathetic letters tell many a tale of economy and contrivance practised. It is easy to believe, therefore, that the Czarina's youth was passed in the most frugal home, and that she led the quiet life of the ordinary German or English girl of the middle-class. A shilling a week was all that she was allowed for pocket-money until after her confirmation, when the allowance was doubled. She was brought up more after the fashion of an English girl than a German girl. Her nurse, Mrs. Orchard, was English, and she also had an English governess, Miss Jackson.

Princess Alix combined the true English love of outdoor sports and pastimes with the musical talent of the German nation, and early developed a gift for art in various forms, being particularly clever with her pencil and brush. At the same time she was instructed in many of the domestic arts, such as cooking, cake-making, plain and fancy sewing, and used to execute the most delicate embroideries. She was born at Darmstadt on June 6, 1872.

Princess Alice made frequent allusions to her youngest daughter in after-letters — “Alicky,” she used to call her. “She is a sweet, merry little person,” she once wrote, “always laughing, and with a deep dimple in one cheek, just like Ernie.” [the present Grand Duke of Hesse]. And on another occasion Princess Alice remarked: “She is quite the personification of her nickname, ‘Sunny.’” The little Princess was so bright and joyous that she was called “Princess Sonnenschein.”

Princess Alix was only six years old when she lost her mother, and, as her elder sisters grew up and married, she became more and more the companion of her father. When he died she stayed a good deal with her sisters, and at the house of the Grand Serge she was thrown into the company of the present Czar, then the Czarewitch. He had been fond of Princess Alix for years. Indeed, it is said that his affection for her dated back to the time when she was a child of twelve, and they met at the Grand Duchess Serge's wedding.

The late Czar, it seems, favoured one of the Montenegrin princesses as a future Empress of Russia, and when he found the Czarewitch was setting his affections in another direction he sent him on a tour round the world, in the hope that fresh scenes would bring fresh thoughts.

But the Czarewitch was not to be turned from his purpose, and on returning to Russia won over the Grand Duchess Serge and the Duchess of Saxe Coburg-Gotha to plead his cause with the Czar and Queen Victoria, who eventually gave their consent to the engagement. The Queen had never been an actual opponent of the marriage, but Princess Alix was delicate and young, and the perils of a Russian throne were great, and for these reasons Her Majesty would have preferred that her granddaughter, of whom she was extremely fond, should have chosen a life of less anxiety.

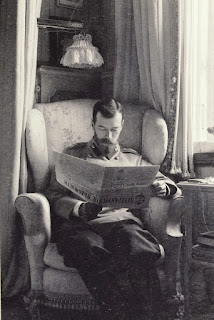

HER MAJESTY THE CZARINA

Another grave reason for objection was the change of religion that such a marriage would involve on the bride's part, and this weighed heavily with Princess Alix herself, and made her waver over and over again in her decision. She clung to the Evangelical faith in which she had been brought up, while an Empress of Russia must necessarily embrace the Greek Orthodox Church. However, heart ultimately prevailed — for the marriage was purely an

affaire du cœur on both sides.

Before starting for the Coburg festivities the Czarewitch said to his parents: “I am determined at last to receive an answer from her lips.”

Princess Alix was won, but it is stated that earnest discussions took place between the lovers on the subject of conversion before the engagement was announced.

Even then religious scruples began to trouble her later, and it seemed almost doubtful if the marriage would really take place. But the Czarewitch was so earnest and persistent, and Princess Alix was so fond of him, that her hesitation was finally overcome. Then she devoted herself to a close study of the Russian language.

Shortly after this came disturbing rumours about the health of the Czar Alexander III, to be followed soon afterwards by Princess Alix's departure for Livadia, where she helped the sorrowful Empress to nurse the dying monarch, and, at his wish, consented that the betrothal ceremony should be carried out without delay.

On being received into the Greek Church, Princess Alix was given the title of Grand Duchess Alexandra Feodorovna. This was one of the most trying periods in the young girl's life, and she won the sympathy of everybody for the peculiarly sad circumstances in which she was placed. At a time that should be, under ordinary circumstances, one of exceptional happiness, the young Princess and her affianced husband were overshadowed by a great sorrow, which naturally robbed their wedding of much of its brilliance. Added to this was the ordeal that Princess Alix was compelled to undergo of her change of religion, to say nothing of her change of position, of parting with old friends, leaving her own country, and taking up life in a comparatively strange land, and among people of whose ways she had yet to learn. Much is expected of an Empress, and the young Princess's task was no light one.

The Emperor Alexander was dead, and the wedding of the new Emperor was, in consequence, celebrated very quietly. It took place in the Winter Palace, St. Petersburg, on November 26th, 1894, not a month after the Czar Alexander's death. The Czarina was twenty-two, the Czar twenty-six, at the time of their marriage.

How wise was the Czar's choice of a Consort has been proved time after time since the wedding. The Czarina is a woman of cool judgement and great power in discerning character. She thinks before she acts, and her advice is always so good and so well-balanced that in her the Czar has found a true helpmate in every sense of the word. She takes life very seriously — as, indeed, who in her place would not? — but she is invariably cheerful and amiable, willing to listen to other people's troubles, and is of the most unselfish character. She is rather above than below medium height, has beautiful regular features, and shares with her sister, the Grand Duchess Serge, the reputation of being one of the loveliest of Queen Victoria's grandchildren. She appears to have completely outgrown her delicacy, and has also lost the slight, fragile appearance that distinguished her as a girl. Her expression is somewhat pensive but very sweet, and there is about her an air of quiet dignity that well becomes her position without in the least bordering on coldness. She has borne on her shoulders the weight of her position in a marvellously cool and confident manner, and it is not too much to say that many of the Czar's best-judged actions have originated from his beautiful Consort.

One of the Czarina's most earnest endeavours has been to ameliorate the lot of the poorer classes of women, and for this purpose she has made herself

au fait with the Poor Laws of the country, and has been the means of doing much good.

Perhaps the happiest hours of the Empress's life are those spent in the nursery with her four sweet little daughters, the Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Anastasia, and Marie. The nation has been disappointed that the Czar has no son, but the Emperor and Empress themselves love their little daughters just as dearly as if they had been heirs to the Crown, though, no doubt, they too would like to secure the throne for a child of their own. On the birth of the Grand Duchess Olga the Czar is reported to have said that he was glad the child was a girl, “because,” said he, “had our child been a boy he would have belonged to the people; being a girl, she belongs to us.” This little girl bears a strong resemblance to her mother, while her sister Tatiana is totally different in lineament, and is more like the Czar.

One of the most beautiful of the Royal country palaces is that of Peterhof, in the grounds of which are innumerable waterfalls and fountains. The Czarskoë Seloe is another perfect palace, where the Czar and his family spend the summer months.

The Czarina, although surrounded with the most luxurious homes of any European Queen, remains perfectly simple in her tastes. She used to be almost Puritanical in her love of simplicity so far as it affects dress, and it was with the utmost difficulty that she could be persuaded to choose a

trousseau befitting an Empress of Russia. Even now she despises over-elaborateness in dress; and although her own wardrobe is necessarily carried out on a magnificent scale, she sets no extravagant fashions to those about her.