Source:

The Emperor Nicholas II as I Knew Him, by Major-General Sir John Hanbury-Williams, 1922

The excerpts:

29th October 1915.

Sat next the Empress at dinner, she having come here for a short visit.

The Empress asked me about my family again this evening, and I told her that to-day was the birthday of my father, who, if he were still alive, would be 116 to-day, as he was born in 1799.

The Empress spoke to me of her indignation at the delay caused to the Empress Mother in her journey to Russia by the German authorities, and of her own determination in those anxious days just before the outbreak of war that the cause of Russia and the Allies was a just one. That she dreaded the horrors of war which must follow there is no doubt, but she stood loyally for Russia throughout.

Her relief when she heard that Great Britain was to be one of the Allies was great. She had always loved our country, and had faith that never wavered of our determination and support.

How far it was her influence that persuaded the Emperor to take personal command of the troops in the field is a vexed question.

I give the account of the Emperor himself to me personally on his decision, and there was no particular call for his telling me the facts as clearly as he did.

--

19th May 1916.

The Empress arrived yesterday and told me how pleased she had been with her visit to the British hospital at Petrograd, and what excellent work Lady Sybil Grey was doing there.

I found the Empress much easier to get on with than I expected, probably for the reason of her great love for my own country, and her custom of talking English constantly to the Emperor, and the many interests she had on matters upon which I was able to give her news or information.

When she told me how terribly shy she felt on coming into the room where we were all assembled — and it was a very large gathering, the chiefs of all the Allied military missions, the French, Belgian, Italian, Japanese, Serbian, and a galaxy of Russian officers, with a sprinkling of Russian officials, both civil and diplomatic — I told her that the Emperor was always there, and then said laughingly to her: 'Your Majesty is so accustomed to visiting hospital cases and seeing operations that the best thing to do is to imagine to yourself that we are only 64 operation cases, and all will go well.'

It is probable that her own shyness, which gives the impression of aloofness, prevents people from talking to her and freezes up conversation.

The moment one began to laugh over things she brightened up and talk became easy and unaffected.

To-day being the Emperor's birthday we all attended a very beautiful service at the garrison church, after which there was a levee, I being the doyen leading in to wish the usual happy returns.

Sir Samuel Hoare arrived on a short visit.

At the birthday dinner I sat next the Empress, who told me a great deal of her hospitals, and of her gardens in the Crimea, from which the wonderful show of flowers which decorated the table came. The Emperor, who sat next the Empress, told me that she sent him flowers every day for his room. They both talk English as their own ordinary means of conversation, and the Empress seemed very well and in good spirits. She asked a great deal about the Duke of Connaught and Canada, and curiously enough on return to my quarters I found a letter from H. R. H. from Canada.

--

16th June 1916.

Another lot of most welcome flowers arrived from the Empress, for which I thanked the Emperor. ...

--

8th July 1916.

Some more beautiful flowers sent me by the Empress.

--

23rd July 1916.

I had an opportunity of thanking the Empress, next to whom I was at dinner, for her kind and continual gifts of flowers to me.

She leaves again to-morrow in her Red Cross car.

The Empress walked in to-night, looking like a beautiful picture, with her daughters. Hers is the only sad face in the family, but it lightens up when she comes by and greets one. To-night, however, she looked as if she had been suffering and was anxious about something.

As I was next to her at dinner, I asked her if she had been working very hard.

She said 'No,' but that she had trouble from her heart and that it alarmed her. Not knowing much of illness of this kind, I merely said that I knew of one case where the person concerned had found that it was merely a muscular trouble and soon passed off.

It seems extraordinary how little it takes to cheer her up, for the conversation turned off on to the subject of pictures and Verestchagin's work, and till the end of dinner she seemed quite happy.

It is a very curious character, a devoted wife and mother, and yet acting under bad influences which react on her, on all that belong to her and her own country.

She is so proud of Russia and so anxious that the Allies should win the war, and yet, without being aware of it, carrying out bad advice in the selection of advisers and others. War to her seems almost more terrible, if such a thing is possible, than to other people. But she spoke of it to me as the 'passing out of darkness into the light of victory.' 'Victory we must have.'

--

25th July 1916.

... The Emperor told me at dinner that the Empress had sent me her best wishes in her daily telegram to him.

--

15th August 1916.

I lunched with the Emperor and Empress, both most kind in urging me to come back as soon as possible. After lunch I walked up and down for a long time with him in the garden, and he gave me various letters and messages from him and the Empress to take to England.

As he said good-bye, he added: 'Tell them in England of our good feeling for them all and of the high appreciation felt here of the splendid work of the British Navy and Army. They must not believe any stories which go about trying to make mischief between the two countries.

'We mean to fight this war out to the end with our good Allies. And the only peace we shall agree to will be one that will do us all honour together when once we have achieved victory.'

The Empress spoke of the education of children, and how anxious she was that her daughters should be simple and unaffected, that in England girls had so many opportunities of healthy out-of-door amusements, and moved about more.

She told me that we must not spoil the little boy, and I assured her that we wouldn't; indeed he was not the sort that is easily spoiled, and his tutor kept him in good discipline.

She feared that the war would sadden their lives, but at the same time saw quite clearly that an experience such as we were going through would impress them without leaving too lasting a sad memory.

'What a responsibility,' she said, 'for those who started this awful war, killing, wounding, suffering, and the dark shadows thrown over young lives, which ought to have nothing but brightness.' She at first could not believe the stories that came from Belgium of the treatment of the civil population by the enemy. 'But now we have proofs, and no punishment can be strong enough for the offenders. Your English soldiers would scorn such ideas of treating even the worst of their enemies in this way.' ...

--

20th October 1916.

The Empress here, and I sat next to her at lunch, when we had a long talk about my visit to England, a country for which she has such great affection and in which she takes so much interest. She also wanted to know all about my family, and especially of the two boys (the elder whom I left, I fear, not far from the end, and the younger one who was so badly wounded). She is indeed most kind, sympathetic and thoughtful for others. She told me that she had not been at all well herself, nerves and heart trouble.

What a difference it would make to Russia if she had good health and nerves.

The Emperor sent for me after lunch and assured me that all was right in Russia, and determination to continue the war to the bitter end as firm as ever. He quite realises the importance, he says, of helping Rumania, and hopes that some forward action from Salonika will help.

He trusts that any rumours as to a premature peace on the part of Russia will be treated for what they are worth, which is nothing. Enemy intrigue is at the bottom of these rumours.

He is as fully determined as are his armies to continue the struggle until Victory is assured. Idle gossip in some centres, such as Petrograd, is not worth heeding, and he hoped that no one in England would be affected by it. German and enemy intrigue was the cause of all the malicious talk.

The Empress had been equally keen in her anxiety for the success of the Allies, and I hope this reassuring report will continue. I told the Emperor that I hoped the Empress would have a long rest, as she seemed overwrought. ...

--

24th October 1916.

The Empress sent me some more flowers, and asked if she could see my children's photographs, which I managed to produce, and the next day when I was with the Emperor at dinner he told me that she was sending me a photo of herself and the little boy.

--

14th November 1916.

... More chrysanthemums and other flowers from the Empress.

--

27th November 1916.

The Empress-Mother's birthday. H. I. M. went to dine with the Empress, and I was able to send a message of thanks for more flowers. ...

--

28th November 1916.

Sat next the Empress at lunch, when she seemed in really good spirits and as kind as ever, asked a great deal about my wounded son, and seemed hopeful about the war. ...

--

1st December 1916.

Their Majesties both congratulated on Queen Alexandra's birthday, and drank her Majesty's health.

--

5th December 1916.

Both Emperor and Empress were present at a cinema performance for the soldiers and were very well received.

In the evening I had a long talk to the Empress, who spoke of the necessity for people keeping cheerful and not losing their heads over the length of the war, which she was convinced would end in the victory of our Allied forces.'

After dinner she beckoned to me to come up and talk to her again. I crossed the room to the piano, where we stood alone. H. I. M. then referred to the wicked slanders that were being spread about in the large towns, but hoped that the recent utterances of Ministers on 'both sides of the water' would convince people of the firm determination of the Allies to see the war through to the bitter end.

She then said: 'You are, I hear, going up to Petrograd on a short visit soon?' 'Yes, your Majesty, I hope to pay a visit and see the Ambassador and hear the news up there.'

'Well, promise me if you go that you will not believe all the wicked stories that are being gossiped about there.'

It gave me the opportunity to say something which I bad in my mind, and which could not have been said had not the opportunity offered itself. It was on my lips when the Emperor came up laughing and said: 'What are you two plotting about in the corner?'

The conversation broke off, as they then bid us good-night and I left.

[N.B.: That was the last occasion upon which I saw the Empress. No doubt if I bad spoken my words would not have had much effect, but I bad been urged to do so by someone much concerned, and had never expected to have the chance.]

--

30th December 1916.

This evening while Charlie Burn, a very old friend whom I was glad to have with me, was sitting in my room (at the Hotel Astoria at Petrograd), I was rung up by Wilton of The Times:

'They have got him at last, General.'

I guessed to whom lie referred.

It was the end of Rasputin.

The year 1917 opened with the death of Rasputin as the talk of Russia.

So much has been written about this notorious scamp that it would only be a tiresome repetition to give a sketch of him here.

He was never allowed to come to the Headquarters of the Armies in the Field.

A brief summary, however, of what I gathered about him, touching as it does, unfortunately, on the life of the Empress, is almost necessary.

As I spent most of my time at Headquarters or in the field, I only paid occasional visits to Petrograd, and naturally did not endeavour to see him, or make inquiries on a question which, being in the mouths of everyone, was sufficiently discussed and talked about to make further probing into it unnecessary.

Since those days I have come to the following conclusions:

His influence over the Empress was undoubted. It arose over the history of the birth of her son a son being granted to her, she thought, owing to the prayers of this wicked and wandering monk.

The delicate health of the young heir was the cause of great anxiety to her, and she placed all her faith on Rasputin to keep the boy in health.

--

JANUARY 1917

It is possible that he had some of the qualities of a 'nerve specialist,' and either through attendance on the invalid, or by his influence over the mother, induced the latter to believe that he was indispensable for her boy's sake.

So gradually he became her adviser on matters of state, and through the Empress his influence affected the Emperor.

How much he was a paid agent of the enemy it is difficult to say, but there is no doubt that he received money from some sources which did good work for Germany at the time, and bad for Russia.

There seems but little doubt that his principal agent at Court was, wilfully or not, the celebrated Madame Vouirobova, who was very rarely away from the Empress.

The known influence he exercised over the Empress, and thus upon the Emperor, made him the court of appeal for all those intriguers and place-seekers who had their own axes to grind, and knew full well that here was a means of assuring their success. No doubt, wherever the money came from, whether from German sources or others, it became well spent by those who, for their nefarious purposes, brought about, by 'slow drops of poison,' as it were, the ruin of Russia.

The public scandal reached its climax in 1916, when he was 'removed' to other spheres, and of the two spheres there can be but little doubt in which he reposes.

And yet it always seems to me, in going back over past history, that the death of Rasputin, however desirable it was on moral and other grounds, was the factor leading to the final debacle of the Romanoffs.

Instead of saving Russia, by another of the ironies of fate which have pursued that great and unfortunate country, it helped to ruin it.

Looking at all the facts coldly and dispassionately, it seems possible that if this 'happy dispatch' had been postponed till a little later — after the war-Russia might have been spared the terrible blow which loyal Russians felt in the desertion by their country of the Allied cause.

But one thing must always be remembered — his dealings with the Empress were those of a bad adviser, an imaginary saint, who she believed, alas! had the interests of her country and of her son at heart.

Some stories of the many published about him were absolutely untrue and unjustified, except to those who wished for a lucrative result from them.

An unscrupulous blackguard, posing as a saint, and, owing to the cures which he apparently effected on the little Tsarevitch, trusted and believed in by the Empress, whose love for her son and naturally nervous temperament made her an easy prey to advice and suggestions from Rasputin affecting political and other appointments, on which she in her turn over-persuaded the Emperor.

The scandals which he had caused led to tales of worse ones, most of the latter being, however, without any foundation.

I never saw him, as he was not permitted to come to the armies, and he was not a person that one was anxious to see.

But anyone who knew the Empress knew full well that she might have been spared many of the wicked accusations which were made concerning her dealings with him.

--

4th January 1917.

In the train last night on my return from Petrograd to Headquarters I travelled with one of the Emperor's A.D.C.'s. He was naturally full of the Rasputin episode, and anxious as to its results. The question is: What will be done with the officers who took part in it? If they suffer in any way there will be trouble. The best thing, as I told my friends, would be to pack them off to their regiments at the front. It is such a peculiar case, reading like a romance of the Middle Ages, that it may lead to any and all sorts of trouble, and it requires a very strong man at Court to place the matter in a clear and impartial light before their Majesties.

The difficulty would be specially with the Empress, being as she is a firm believer in the good faith of Rasputin. And her influence reacts on the Emperor.

I confess that even with the disappearance of the most important factor in the drama I see no light ahead yet, and the situation may develop into anything. ...

The crowned heads of this country are so far from their people, and the Empress through shyness and a nervous nature is but rarely seen, though she has worked splendidly for the sick and wounded, and has a really kind and sympathetic nature, which unfortunately no one experiences except those who are very near her, or who happen to have seen a good deal of her, as I have done.

Shyness gives at once the impression of aloofness, with the result that it 'puts off' anyone getting to know her or being able to tell her things she should know.

At present she stands alone. It is a sad business, and when one looks at those pretty daughters one wonders what will happen to them all. ...

--

11th January 1917.

As the Russian New Year falls in two days wrote to-day to my old friend, Count Fredericks, to ask him to convey my respectful good wishes to the Emperor and Empress.

I said that I hoped that the new year might bring us the peace which I knew they wished to see brought about by our victorious arms, and I added that I hoped their Imperial Majesties would always find good advisers to help them in times of difficulty. ...

--

It is difficult to offer an estimate of character of the one without the other. More difficult, perhaps, to speculate upon what would have happened if they had never met, and he had found another consort.

The Emperor — till too late — was a confirmed autocrat, apart, I believe, from the influence of the Empress, who had identical views as to the government of the country.

In a speech made in January 1895 he had said: 'Let them [the people] know that I, devoting all my efforts to the prosperity of the nation, will preserve the principles of autocracy as firmly and unswervingly as my late father of imperishable memory.'

It was the teaching of his boyhood, and he felt it his duty to hand these principles on.

It is possible, however, that had he married someone else, possessed of a clear head and the influence which might have been exercised with him by one who, though not a courtier, was so near him as to be available at any time to suggest and advise, circumstances might have worked out quite differently. As it was, even a courtier who had the good sense to speak out with honest endeavour — and how rare such courtiers are to be of service went to the wall. Whether that was the independent action of the Emperor alone, or of some additional pressure from the Empress, I do not know. The fact remains that an already confirmed autocrat became more so under her influence.

That they honestly believed that it was the right system for the government of their country is certain. Thus there existed a couple working hand in hand, as they believed and imagined, for the good of their country, and the dangers of the autocratic system became intensified by the fact that the stronger influence of the two was that of the Empress, whose ill health and neurotic character not only cut her off from the outside world of Russia, but brought her under other influences, which reacted again upon the Emperor and finally brought him, loyal and devoted as he was, to his fall.

Appointments and dismissals of ministers lay entirely in the hands of the Emperor, but the adviser who brought them about was in most cases the Empress.

The combination of an Emperor so devoted to his Empress that her word was law, and of an Empress led unconsciously by the worst possible advisers, brought about their ruin and that - for the time being - of their country.

According to M. Gilliard's account of the last days of the Imperial family, those fine qualities of the Empress which showed themselves in her care and devotion to the sick and wounded during the war became still more evident in the days of distress, misery and ignominy which crowned the end.

Even her critics and her enemies, and she had many, will accord her a meed of praise for the courage and devotion which, even in what must have been the most intense purgatory to her, she showed unselfishly for her husband and children.

And so in death they were not divided.

I was much struck, closely interested as I was in Russian affairs, at the apparent lack of interest, almost amounting to indifference, with which the news of the fate of the Russian Imperial family was received in England. It was probably to be accounted for by two reasons, the number and rapidity of the march of events connected with a great war and its sequences, and the uncertainty as to the truth of the reports, confirmation or contradiction being almost daily reported, till a lack of interest ensued.

The fact remains, however, that one of the greatest tragedies in history was, to all appearances, quickly forgotten, except by those to whom it came very near.

As to the alleged pro-Germanism of the Emperor and Empress, I think I have said enough in the preceding pages to dispel the idea of this accusation.

I may add another note upon the subject.

As is known to those taking an interest in the question, a commission was appointed by the Revolutionary Government with the duty assigned to it of searching through all the letters, both official and private, of the Emperor and Empress.

The Commission apparently did its work with zeal and such enthusiasm as can be found by those who enjoy the prying into the personal and private and family affairs of other people.

No doubt, all agog for some scandalous discovery, or proof of guilt by the discovery of letters to the enemy, or expressions of affection for the Germans, they scanned the pages before them, word for word.

What was the result?

M. V. M. Roudnieff, one of its members, allowed indignation to master his surprise, and published his personal report, proving to the world at large that not a jot or a tittle of evidence was to be found.

The mysterious intrigues of the Empress with the enemy vanished.

The accusations of disloyalty on the part of the Emperor were exploded.

Those who knew them received this news with no surprise. Those who professed to know them, and maligned them, probably preferred to look elsewhere for any other kind or other sort of news they could find.

What followed? The irony of fate threw the country where accusations of disloyalty had dethroned an Emperor and Empress, into the arms of the very enemy with whom they had been supposed to intrigue, and Brest-Litovsk and Bolshevism ruined Russia.

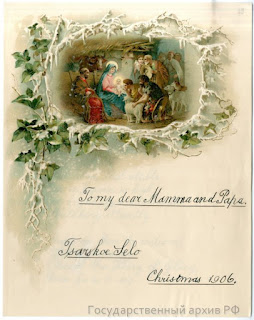

Above: Alexandra.

Above: Major-General Sir John Hanbury-Williams.

Above: Nicholas and Alexandra.

Above: Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia.

Above: Alexei.

Above: Grigori Rasputin.

Enable GingerCannot connect to Ginger Check your internet connection

or reload the browserDisable in this text fieldEditEdit in GingerEdit in Ginger