Source:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101059280824&view=1up&seq=698

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101059280824&view=1up&seq=699

The articles:

THE ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS.

LONDON: SATURDAY, DECEMBER 21, 1878.

—

The Country is in mourning — The Country mourns. How great a difference there may be between the two states — the outward and the inward — need not be pointed out. There is no difference in the present instance. The "trappings of woe" correspond but too closely with the sorrow of the heart. Princess Alice of Great Britain and Ireland, the Grand Duchess of Hesse-Darmstadt, the second daughter of Queen Victoria, has been removed from the present life by the terrible malady which had, a few days before, carried off her youngest daughter and which had put in sore peril the lives of her husband and the rest of her children. The lamentable event occurred on the anniversary of her father's death, seventeen years ago. It brings with it touching reminiscences which will now be closely associated with the memory of her life. How she nursed the Prince Consort in his mortal illness, how the tenderness and self-sacrificing devotion of her love smoothed his passage from this world to the next, how she upheld her Royal Mother under the fresh burden of her widowhood, how ten years afterwards she nursed her brother the Prince of Wales, and was happily rewarded by the restoration of his health, we all know. And now she has herself fallen a victim to the very virtues which commended her to our hearts. There is a pathos in the incident mentioned by Lord Beaconsfield in the House of Lords on Tuesday last which is simply irresistible. "The physicians," he said, "who permitted her to watch over her suffering family enjoined her under no circumstances whatever to be tempted into an embrace. Her admirable self-restraint guarded her through the crisis of this terrible complaint in safety. She remembered and observed the injunctions of her physicians. But it became her lot to break to her son, quite a youth, the death of his youngest sister, to whom he was devotedly attached. The boy was so overcome with misery that the agitated mother clasped him in her arms, and thus received the kiss of death." Her illness was watched with painful anxiety, not in her adopted country only, but in that of her early home. Medical science, however, was unable to stay the progress of her disease. The conflict is over. Death has gathered into his arms all that was mortal of the Royal Princess, and the Court and the people of this country share between them the sorrow which arises from the irreparable loss occasioned by her decease.

Yet not a loss only, or wholly, nor a gloom entirely unrelieved. The dark cloud has its "silver lining." Even what we see on this side of the grave, distressful as it is to many, grievous to all, is yet spanned by a bow of promise. The life of Princess Alice is even now far from having worked out its beautiful results. It was a life of blessing to all who came within its sphere, and of potent influence for good to those who were outside of it. Her exalted position was but the accident which displayed it more vividly and more widely than would otherwise have been the case. Its genuine lustre was in itself. It would have been charming anywhere, in any rank, in association with any circumstances, but it was rendered more conspicuous in that it was lifted up on high. We need not speak in a depreciating tone of the external grandeur — albeit grandeur in simplicity — the centre of which she so exquisitely adorned. They who were nearest to her either by the ties of relationship or by the privilege of personal intercourse, speak admiringly of her intellectual culture, her solid judgment, her brilliant vivacity. We can believe them. But that which most attracts and fixes the regard of most men was the tender and ever outflowing sympathy which she had for all kinds of human suffering. An ornament to her Court, a bright and sparkling gem in her family, diffusing gladness wherever she vouchsafed her presence, she was always ready, in the alleviation of sorrow, to take the post demanding the greatest self-denial and to meet the troubles from which she might have been excused had she shrunk from them. "So good, so kind, so clever," says the Prince of Wales, in a letter written on the day of her death — words of simple testimony to her worth which find an echo in the bosom of every subject in the realm. She was a feminine exposition of the spirit of "Albert the Good," and her death brings back to us in full flush the grateful remembrances we have of his life.

The blow, as might have been expected, has been a heavy one for the Queen. The day on which it occurred necessarily reopened the deep wound made upon her domestic happiness, never perhaps to be completely healed, by the death of the Prince Consort. Her people rejoice in the assurance that her Majesty's usual health has not shown any indications of giving way under the stroke. They are thankful that she had an opportunity, as late ago as last autumn, of seeing and exchanging embraces with her beloved daughter. They are fully sensible that it is out of their power to offer her such consolation as will reach to the depth of her affliction. They are willing to bear her grief, if that were possible; but, that not being so, they are anxious to share it. They well know that they owe much to her, but they know not how much. They looked on with admiring and even affectionate sympathy whilst she was engaged in training her children for the high positions which they occupy. They cannot see her in domestic trouble without yearning to give her such solace as their unanimous participation in her grief may help to afford. The light which the light of Princess Alice casts forward, as a glorious example upon their several households, beams also in its reflex radiance upon the family life and maternal influences of their beloved Sovereign. They owe to her an untold sum of thankfulness, and they cannot allow her daughter to pass away from earth without becoming increasingly sensible of the debt of obligation under which the mother in her child has laid them. With more fervency than ever they will now repeat the refrain of the National Anthem, "God Save the Queen."

The lesson of the late Princess's life is as noble as it is obvious. Moral worth is a far more felicitous distinction than high position. It is well when both are combined, as in her case; but the first claims our reverential homage even when quite apart from the last. The women of society are not the only persons who may profit from what they have been called within the last week to witness. Love is the surest parent of love. To be lovely is the best forerunner of lovely action. Influence, honour, and unfailing satisfaction are to be acquired, not so much by the triumphs of ambition as by the quiet discharge of daily duties, and by the unostentatious but continuous outflow of a loving heart. In this respect to give is to receive, to bless is to be blessed, and in the words of Holy Writ, to lose life is to find it.

...

THE DEATH OF PRINCESS ALICE.

The whole English nation, and, we believe, the German nation also, have since last Saturday joined with our Queen and the Royal family, and with the bereaved husband and children at Hesse-Darmstadt, in heartfelt mourning for the untimely death of this illustrious lady. Her Royal Highness was, to quote the touching words of her brother, the Prince of Wales, in letter which Earl Granville read on Tuesday evening to the House of Lords, "so good, so kind, so clever!" As daughter, sister, wife, and mother, she had ever shown the characteristic virtues of womanhood; and she had laboured, both in England and in Germany, with a "thoughtful beneficence," to relieve the sufferings of the sick poor in hospitals, of wounded soldiers, and prisoners of war, at the same time cultivating every pursuit of refined intelligence and taste, and the graceful accomplishments befitting her exalted rank. The dates and other details of her personal history will be found set forth in the usual form of an Obituary Notice. Our leading article this week is naturally devoted to this topic, which has, more than all other contemporary affairs, occupied the public mind; while the votes of condolence in both Houses of Parliament, with the appropriate speeches of Lord Beaconsfield and Lord Granville, in the one instance, of Sir Stafford Northcote and Lord Hartington in the other, are recorded as an authoritative testimony of national regret, and of profound sympathy with the Royal Mother, for whom we have never ceased, these seventeen years past, to feel the reverential tenderness due to a Royal Widow.

Her Royal Highness died a little before eight o'clock in the morning last Saturday, in the Grand Ducal Palace at Darmstadt, her state the day before having been such as to give rise to the greatest alarm with increased fever and the swelling having extended to the windpipe or larynx. She had been ill since just after the death of her youngest child, Princess Maria Victoria, a little girl of four years, who had, with others of the family, been attacked by diphtheria. Upon the death of her little one the affectionate mother herself went to the bedside of her son, Prince Ernest, who is ten years of age, and who was suffering from the same disease. It appears to have been upon the occasion of this sorrowful interview, and by a kiss from the poor innocent boy, which his mother could not refuse at such a moment, that the germs of the terrible malady were conveyed to her system.

The sad intelligence was received at Windsor Castle on Saturday morning. The Queen had received previous telegrams from Sir William Jenner to explain to her Majesty the significance of the symptoms observed.

Immediately on the event becoming known in London the Home Secretary wrote to the Lord Mayor communicating the fact, and requesting him to give directions for the tolling of the great bell of St. Paul's Cathedral. His Lordship also read the letter from his seat in the Justice Room of the Mansion House, and a copy was posted outside the building.

On Sunday morning and evening, in their pulpit discourses, particular allusions to the mournful event were made by Canon Liddon, at St. Paul's; by Canon Prothero, at Westminster Abbey; by the Rev. H. White, at the Chapel Royal, Savoy; by Canon Spencer, at the Temple Church; by Canon Farrar, at St. Margaret's, Westminster; by the Bishop of Columbia, at St. Stephen's, Westminster; and at most other churches and chapels in the metropolis and throughout the country.

At Darmstadt, on Tuesday, the funeral solemnities in connection with the burial of Princess Alice commenced. The body was removed from the Grand Ducal Palace to the church within the old castle, where the religious ceremony was to take place next day. The hearse was preceded by a half-squadron of Dragoons and a number of Court officials, and was followed by the Royal carriages and another half-squadron of Dragoons. The torches were carried on either side of the hearse by six servants, and some non-commissioned officers of the Guard made up two lines of escort. There had been a heavy fall of snow during the day, but the night was almost cloudless. The whole of the route to the church was lined with spectators, who respectfully uncovered as the procession passed. The Princess was well known to the inhabitants of Darmstadt, not only through frequently being seen in the town with her husband, but by reason of the personal interest which she took in the local charities and other institutions. The procession having arrived at the church, the coffin, covered with a crimson pall, was placed on a black velvet catafalque, bearing the Grand Ducal crown and the arms and orders of the Princess, and throughout the night was attended by a guard of honour. Between nine o'clock and noon on Wednesday the church was open to the public, and during that time some thousands of persons passed reverently by the coffin. By two o'clock, the hour fixed for the reading of the burial service, the edifice was filled with the nobility, members of the diplomatic corps, the Ministry, military officers, Privy Councillors, members of the two Chambers, the Mayors of Darmstadt and other towns, the municipal councillors, the President of the National Synod, and a deputation of the clergy, officials of the palace, representatives of Ministerial departments, and deputations from various regiments. The right side of the altar was occupied by members of the Women's Union for Nursing Sick and Wounded in War, founded by the Grand Duchess and bearing her name; on the left were ranged ladies who had been presented at Court. Everything being in readiness for the service, the mourners — the Grand Duke of Hesse, the Prince of Wales, Prince Leopold, Prince Christian of Holstein, and the Grand Dukes of Mecklenburg and Baden among others — entered the church, and were conducted to their places with the ceremonies usually observed on such occasions. The Crown Prince and Princess of Germany were not present, the Emperor William having, after a consultation with his physicians, declined to permit them to attend the funeral on account of the risk of infection. In their absence the Imperial family were represented by General Goltz, Colonel Panwitz, Count Matuschka, and Count Seckendorff. M. de Quaade was in attendance for the King of Denmark, General Burnell for the King of the Belgians, and Baron von Perglas and Count Durkheim for the King and Queen Dowager of Bavaria. The Burial Service, to which some anthems and chorales were added, was performed by Assistant Chaplain Grein, one of the Ducal chaplains, and the Rev. Mr. Sillitoe, the resident English clergyman. The coffin was then removed from the catafalque to a hearse drawn by eight horses, and the sad procession passed to Rosenhohe by way of the Market-place, the parade-ground, the Alexanderstrasse, the Muehlstrasse, and the Erbachsterstrasse. The route was densely lined with spectators, and the utmost order prevailed.

During the funeral ceremony at Darmstadt and Rosenhohe a solemn service was held at Windsor Castle.

From all parts of the country we have reports of resolutions of condolence carried by Town Councils and other bodies. Minute guns were fired on Wednesday at Woolwich, Chatham, Portsmouth, and Devonport, and the flags of her Majesty's and other ships were flown half-mast high.

We present on the front page of this week's Number the portraits of the lamented Princess Alice and her youngest child, both so lately taken from their afflicted family; and our Extra Supplement consists of a separate Portrait of her Royal Highness, for which, as well as for the subject of our front-page Engraving, we are indebted to a photograph by Mr. Alexander Bassano, of Piccadilly.

Thursday, May 28, 2020

Tuesday, May 26, 2020

Alexandra's 1897 summer dress, then and now

Source:

Photos courtesy of Olga Grigor'eva at lastromanovs on VK

https://vk.com/lastromanovs?w=wall-56510987_50566

Summer dress. Made of white chiffon on a lilac silk cover, decorated on bodice, skirt and sleeves, embroidered and woven lace applique in the form of an ornament of leaves and flower branches. Front collar with a frill. The front of the bodice is pleated, with a lace frill in the form of a fichu; lace frills on the shoulders. The long sleeve is pleated, with a frill at the brush. On the skirt, the side wedges are trimmed with lace.

Workshop "A. Brisac".

St. Petersburg, 1897

Photos courtesy of Olga Grigor'eva at lastromanovs on VK

https://vk.com/lastromanovs?w=wall-56510987_50566

Summer dress. Made of white chiffon on a lilac silk cover, decorated on bodice, skirt and sleeves, embroidered and woven lace applique in the form of an ornament of leaves and flower branches. Front collar with a frill. The front of the bodice is pleated, with a lace frill in the form of a fichu; lace frills on the shoulders. The long sleeve is pleated, with a frill at the brush. On the skirt, the side wedges are trimmed with lace.

Workshop "A. Brisac".

St. Petersburg, 1897

Ledger of parcels sent by Alexandra from 1897 to 1905

Source:

https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2018/russian-works-of-art-faberg-icons-l18113/lot.429.html

Comprising 168 pages with printed headings 'To whom' and 'Signature' in Russian, the 713 individual entries inscribed in various hands in Russian, German, French and English, from 4 December 1897 to 22 December 1905, the first page inscribed in Russian 'From the wardrobe of Her Imperial Highness Empress Alexandra Feodorovna', leather wallet-style binding.

This newly discovered original document provides fresh insight into the life of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, her generous and thoughtful nature, and her shopping habits. It lists the parcels she sent, with dates and recipients, presumably recorded by her ladies-in-waiting. The whole of her and the Emperor’s extended families appear, including her brother and sisters and their spouses, first and second cousins, her grandmother Queen Victoria, and her wide circle of friends, many from her childhood. There are several entries of packages to retailers across Europe. The Empress was shopping on approval, returning things she did not wish to keep, and some things may have been sent for repairs. There are fourteen entries to Fabergé, half occurring in the autumn of 1900. Touchingly, she sent an annual package of goods to the hospital her late mother had founded, Princess Alice’s Hospital in Darmstadt, probably as part of a fundraising drive.

There was of course a flurry of sending gifts around Christmas time, and the dates of many of the entries correspond to the recipient’s birthday. For example, there are three parcels to Queen Victoria, listed simply as ‘The Queen’, on 4 May 1898, sent to Balmoral, 5 December 1898, Osborne, and 6 May 1899, Windsor Castle; Queen Victoria’s birthday was 24 May. (There is an entry for ‘Osborne’ on 18 December 1897, a parcel which was also presumably a Christmas gift to the Queen.) One of these parcels may have contained the jewelled rock crystal desk clock in the Royal Collection (RCIN 40100) which is known to have been a gift from the Empress to her grandmother.

Although only a handful of entries include mention of the contents, in some cases, the contents of the parcels can be surmised from surviving objects known to have been gifts from the Empress and with their dates recorded. The Fabergé gold cigarettes case with plique-à-jour enamel dragonflies (included in the 2016 Schloss Fasanerie exhibition and illustrated, ex. cat. Fabergé Geschenke der Zarenfamilie, Eichenzell, 2016, no. 58, p. 124) which she gave to her brother and which she had engraved ‘For darling Ernie from Nicky + Alix xmas 1900’ is listed in Fabergé’s invoice to the Imperial Cabinet with a purchase date of 30 November 1900. It was almost certainly in the package which she sent to her brother the following day, 1 December 1900. Her Christmas gift to her sister Victoria, Princess Louis of Battenberg, a Fabergé silver case inscribed in enamel ‘Alix/ Weihnachten/ 1904’ (illustrated, ibid., no. 3, p. 51), was certainly included in the parcel she sent to her on 7 December 1904, in a spree of postings on that day which also included parcels to her uncle and her husband’s aunt, Kind Edward VII and Queen Alexandra.

In addition to Fabergé, other retailers listed include the jewellers Bolin and Butz in St Petersburg; Madame Brissac, the leading couturière in St Petersburg, who made the Empress’ gowns; several other St Petersburg shops including Weiss, Tehran, Zhidkov, Malm, Alexander, and the furrier Greenwald; the photographer Pazetti; Maison Spritzer in Vienna; Maison Morin-Blossier, Paris; Edwards & Sons, who made vanity cases and jewellery in London; the jewellers Koch in Frankfurt and Wondra in Darmstadt; Walter Thornhill, dressing cases, London; the firm of Sir Pryce Pryce Jones of Newton, North Wales, who sold flannel to Queen Victoria, who knighted him in 1887, and Royal households across Europe; the London milliner Robert Heath; Pavel Buré, watches, St Petersburg; a shoemaker called Vels; Grachev, silver, St Petersburg; the Avantso shop in Moscow; Swears & Wells, makers of hosiery and gloves in London; Romanes and Patterson, Edinburgh, for tartans and cashmere; Egerton Burnette of Wellington, Somerset, who produced clothes and other soft goods; and Green & Abbott, Oxford Street, London, for chintzes and Chinese wallpaper.

The last entry, on 22 December 1905, rather poignantly, given their relationship, was to her mother-in-law, always listed in the ledger with her full style and title, who was in Copenhagen to avoid the unrest in Russia — 1905 was ‘a year of nightmares’ for the Dowager Empress — and spent Christmas there. The date corresponds to that of a letter, which was certainly enclosed in the parcel, from her son, who writes, ‘All my prayers are with you for the forthcoming holidays. This is the second time that I have to spend Christmas without you. The first time was when you were at home and we were away in India. Very sad not to have your Christmas tree again this year; it used to be so cosy upstairs at Gatchina during these holidays’ (E. Bing, ed., The Letters of Tsar Nicholas and Empress Marie, London, 1937, p. 205).

https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2018/russian-works-of-art-faberg-icons-l18113/lot.429.html

Comprising 168 pages with printed headings 'To whom' and 'Signature' in Russian, the 713 individual entries inscribed in various hands in Russian, German, French and English, from 4 December 1897 to 22 December 1905, the first page inscribed in Russian 'From the wardrobe of Her Imperial Highness Empress Alexandra Feodorovna', leather wallet-style binding.

This newly discovered original document provides fresh insight into the life of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, her generous and thoughtful nature, and her shopping habits. It lists the parcels she sent, with dates and recipients, presumably recorded by her ladies-in-waiting. The whole of her and the Emperor’s extended families appear, including her brother and sisters and their spouses, first and second cousins, her grandmother Queen Victoria, and her wide circle of friends, many from her childhood. There are several entries of packages to retailers across Europe. The Empress was shopping on approval, returning things she did not wish to keep, and some things may have been sent for repairs. There are fourteen entries to Fabergé, half occurring in the autumn of 1900. Touchingly, she sent an annual package of goods to the hospital her late mother had founded, Princess Alice’s Hospital in Darmstadt, probably as part of a fundraising drive.

There was of course a flurry of sending gifts around Christmas time, and the dates of many of the entries correspond to the recipient’s birthday. For example, there are three parcels to Queen Victoria, listed simply as ‘The Queen’, on 4 May 1898, sent to Balmoral, 5 December 1898, Osborne, and 6 May 1899, Windsor Castle; Queen Victoria’s birthday was 24 May. (There is an entry for ‘Osborne’ on 18 December 1897, a parcel which was also presumably a Christmas gift to the Queen.) One of these parcels may have contained the jewelled rock crystal desk clock in the Royal Collection (RCIN 40100) which is known to have been a gift from the Empress to her grandmother.

Although only a handful of entries include mention of the contents, in some cases, the contents of the parcels can be surmised from surviving objects known to have been gifts from the Empress and with their dates recorded. The Fabergé gold cigarettes case with plique-à-jour enamel dragonflies (included in the 2016 Schloss Fasanerie exhibition and illustrated, ex. cat. Fabergé Geschenke der Zarenfamilie, Eichenzell, 2016, no. 58, p. 124) which she gave to her brother and which she had engraved ‘For darling Ernie from Nicky + Alix xmas 1900’ is listed in Fabergé’s invoice to the Imperial Cabinet with a purchase date of 30 November 1900. It was almost certainly in the package which she sent to her brother the following day, 1 December 1900. Her Christmas gift to her sister Victoria, Princess Louis of Battenberg, a Fabergé silver case inscribed in enamel ‘Alix/ Weihnachten/ 1904’ (illustrated, ibid., no. 3, p. 51), was certainly included in the parcel she sent to her on 7 December 1904, in a spree of postings on that day which also included parcels to her uncle and her husband’s aunt, Kind Edward VII and Queen Alexandra.

In addition to Fabergé, other retailers listed include the jewellers Bolin and Butz in St Petersburg; Madame Brissac, the leading couturière in St Petersburg, who made the Empress’ gowns; several other St Petersburg shops including Weiss, Tehran, Zhidkov, Malm, Alexander, and the furrier Greenwald; the photographer Pazetti; Maison Spritzer in Vienna; Maison Morin-Blossier, Paris; Edwards & Sons, who made vanity cases and jewellery in London; the jewellers Koch in Frankfurt and Wondra in Darmstadt; Walter Thornhill, dressing cases, London; the firm of Sir Pryce Pryce Jones of Newton, North Wales, who sold flannel to Queen Victoria, who knighted him in 1887, and Royal households across Europe; the London milliner Robert Heath; Pavel Buré, watches, St Petersburg; a shoemaker called Vels; Grachev, silver, St Petersburg; the Avantso shop in Moscow; Swears & Wells, makers of hosiery and gloves in London; Romanes and Patterson, Edinburgh, for tartans and cashmere; Egerton Burnette of Wellington, Somerset, who produced clothes and other soft goods; and Green & Abbott, Oxford Street, London, for chintzes and Chinese wallpaper.

The last entry, on 22 December 1905, rather poignantly, given their relationship, was to her mother-in-law, always listed in the ledger with her full style and title, who was in Copenhagen to avoid the unrest in Russia — 1905 was ‘a year of nightmares’ for the Dowager Empress — and spent Christmas there. The date corresponds to that of a letter, which was certainly enclosed in the parcel, from her son, who writes, ‘All my prayers are with you for the forthcoming holidays. This is the second time that I have to spend Christmas without you. The first time was when you were at home and we were away in India. Very sad not to have your Christmas tree again this year; it used to be so cosy upstairs at Gatchina during these holidays’ (E. Bing, ed., The Letters of Tsar Nicholas and Empress Marie, London, 1937, p. 205).

Alexandra's letter to Nicholas, dated November 23, 1914, and Nicholas's telegrammed reply

Sources:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=inu.30000011396573&view=1up&seq=81

http://www.alexanderpalace.org/letters/november14.html

Alexandra wrote this letter to Nicholas on November 23, 1914. He sent a telegram in reply the next day.

The letter:

Tsarskoje Selo, Nov. 23nd 1914, Sunday

My own beloved Darling,

We returned here safely at 9¼, found the little ones well and cheery. The girls have gone to Church — I am resting, as very tired, slept so badly both nights in the train — this last we tore simply, so as to catch up an hour. Well, I shall try to begin from the beginning. — We left here at 9, sat talking till 10, and then got into our beds. Looked out at Pskov and saw a sanitary train standing — later one said we passed also my train, which reaches here to-day at 12½. Arrived at Vilna at 10¼ — Governor and military, red cross officials at station, I cought sight of 2 sanitary trains, so at once went through them, quite nicely kept for simple ones — some very grave cases, but all cheery, came straight from battle. Looked at the feeding station and ambulatory. — From there in shut motors driven (I was just interrupted, Mitia Den came to say goodbye) to the Cathedral where the 3 Saints lie, then to the Image of the Virgin, (the climb nearly killed me) — a lovely face the Image has (a pitty one cannot kiss it). Then to the Polish Palace hospital — an immense hall with beds, and on the scene the worst cases and on the gallery above officers — heaps of air and cleanly kept. Everywhere in both towns one kindly carried me up the stairs which were very steep. Everywhere I gave Images and the girls too. — Then to the hospital of the red cross in the Girls gymnasium, where you found the nurses pretty — lots of wounded — Verevkin's both daughters as nurses. His wife could not show herself, as their little boy has a contagious illness; his aids wife replaced her. No acquaintances anywhere. The nurses sang the hymn, as we put on our cloaks; the Polish ladies do not kiss the hand. Then off to a small hospital for officers (where Malama and Ellis had layn before). There one officer told Ania he had seen me 20 years ago at Simferopol, had followed our carriage on a bicycle and I had reached him out an apple (I remember that episode very well) such a pitty he did not tell me — I remember his young face 20 years ago, so could not recognise him. From there back to the station we could not go to more, as the 2 sanitary trains had taken time. Valuyev wanted me to see their hospital in the woods, but it was too late. Artsimovitch turned up at the station thinking I would go to a hospital where sisters from his government were. I lunched and dined always on my bed. At Kovno the charming commandant of the fortress (no Governor counts there now, as it is the active front) and military authocraties, some officers, Shirinsky and Stchepotiev stood there too. The others had been just sent out to town expeditions, close to Thorn to blow up a bridge and the other place I forget, such a pitty to have missed them. Voronov, we passed at Vilna in the street. Again off in motors, flying along to the Cathedral (from Vilna we let know we were coming) — carpet on the stairs, trees in pots out, all electric lamps burning in the Cathedral, and the Bishop met us with a long speach. Short a Te Deum, kissed the miraculous Image of the Virgin and he gave me one of St. Peter and St. Paul, after whom the Church is named — he spoke touchingly of us »the sisters of mercy« and called wify a new name, »the mother of mercy«, Then to the red cross, simple sisters, skyblue cotton dresses — the eldest sister, a lady just come there, spoke to me in English, had been a sister 10 years ago and seen me there, as my old friend Kirejev had asked me to receive her. Then to another little wing of the hospital in another street. Then to a big hospital about 300 in the bank — looked so strange to see the wounded amongst such surrounding of a former bank. One lancer of mine was there. Then we went to the big military hospital, tiny service and wee speech. Lots of wounded and 2 rooms with Germans, talked to some. From there to the station, on the platform stood the companies (I had begged for them, I must confess), so difficult to recognise them, and not many acquaintances, you saw them. Simonin looked a dear. The boatswain of the »Peterhof« with the St. George's cross — all well, Shirinsky too looks well. The Commandant is such a nice simple kind, not fussy man. Begged me to send still 3000 Images by our sailors at a fortress-station, they dressed as soldiers, we as nurses, stopped and looked at the feeding station and barracks hospitals at station and service in wee Church. Some heavy cases. The Livland committee — (Pss. Schetvertinskaya at the head, her property is close by), the daugther as nurse. — At 2 we stopped at a station, I discovered a sanitary train and out we flew, climbed into the boxcars. 12 men lying comfortably, drinking tea, by the light of a candle — saw all and gave Images — 400. An ill Priest too was there — »Zemsky« train, 2 sisters (not dressed as such) 2 brothers of mercy, 2 doctors and many sanitaries. I begged pardon for waking them up, they thanked us for coming, were delighted, cheery, smiling and eager faces. So we were an hour late and cought it up in the night, so that I was rocked to and fro, and feared we should capsize.

So now I saw Irina, after which must meet my Sanitary train. Ella arrives to morrow evening. God bless and protect you — no news from you since Friday. Very tenderest, fondest kisses from your very own old wify

Sunny.

Victoria sends love, living Kent House Isle of Wight.

Messages to N. P.

Nicholas's telegrammed reply:

Telegram.

Stanichnaia. 24 November, 1914.

Have spent three happy hours at Ekaterinodar. Thanks for telegram. I remember about Olga. Embrace you all closely.

Nicky.

Above: Nicholas and Alexandra.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=inu.30000011396573&view=1up&seq=81

http://www.alexanderpalace.org/letters/november14.html

Alexandra wrote this letter to Nicholas on November 23, 1914. He sent a telegram in reply the next day.

The letter:

Tsarskoje Selo, Nov. 23nd 1914, Sunday

My own beloved Darling,

We returned here safely at 9¼, found the little ones well and cheery. The girls have gone to Church — I am resting, as very tired, slept so badly both nights in the train — this last we tore simply, so as to catch up an hour. Well, I shall try to begin from the beginning. — We left here at 9, sat talking till 10, and then got into our beds. Looked out at Pskov and saw a sanitary train standing — later one said we passed also my train, which reaches here to-day at 12½. Arrived at Vilna at 10¼ — Governor and military, red cross officials at station, I cought sight of 2 sanitary trains, so at once went through them, quite nicely kept for simple ones — some very grave cases, but all cheery, came straight from battle. Looked at the feeding station and ambulatory. — From there in shut motors driven (I was just interrupted, Mitia Den came to say goodbye) to the Cathedral where the 3 Saints lie, then to the Image of the Virgin, (the climb nearly killed me) — a lovely face the Image has (a pitty one cannot kiss it). Then to the Polish Palace hospital — an immense hall with beds, and on the scene the worst cases and on the gallery above officers — heaps of air and cleanly kept. Everywhere in both towns one kindly carried me up the stairs which were very steep. Everywhere I gave Images and the girls too. — Then to the hospital of the red cross in the Girls gymnasium, where you found the nurses pretty — lots of wounded — Verevkin's both daughters as nurses. His wife could not show herself, as their little boy has a contagious illness; his aids wife replaced her. No acquaintances anywhere. The nurses sang the hymn, as we put on our cloaks; the Polish ladies do not kiss the hand. Then off to a small hospital for officers (where Malama and Ellis had layn before). There one officer told Ania he had seen me 20 years ago at Simferopol, had followed our carriage on a bicycle and I had reached him out an apple (I remember that episode very well) such a pitty he did not tell me — I remember his young face 20 years ago, so could not recognise him. From there back to the station we could not go to more, as the 2 sanitary trains had taken time. Valuyev wanted me to see their hospital in the woods, but it was too late. Artsimovitch turned up at the station thinking I would go to a hospital where sisters from his government were. I lunched and dined always on my bed. At Kovno the charming commandant of the fortress (no Governor counts there now, as it is the active front) and military authocraties, some officers, Shirinsky and Stchepotiev stood there too. The others had been just sent out to town expeditions, close to Thorn to blow up a bridge and the other place I forget, such a pitty to have missed them. Voronov, we passed at Vilna in the street. Again off in motors, flying along to the Cathedral (from Vilna we let know we were coming) — carpet on the stairs, trees in pots out, all electric lamps burning in the Cathedral, and the Bishop met us with a long speach. Short a Te Deum, kissed the miraculous Image of the Virgin and he gave me one of St. Peter and St. Paul, after whom the Church is named — he spoke touchingly of us »the sisters of mercy« and called wify a new name, »the mother of mercy«, Then to the red cross, simple sisters, skyblue cotton dresses — the eldest sister, a lady just come there, spoke to me in English, had been a sister 10 years ago and seen me there, as my old friend Kirejev had asked me to receive her. Then to another little wing of the hospital in another street. Then to a big hospital about 300 in the bank — looked so strange to see the wounded amongst such surrounding of a former bank. One lancer of mine was there. Then we went to the big military hospital, tiny service and wee speech. Lots of wounded and 2 rooms with Germans, talked to some. From there to the station, on the platform stood the companies (I had begged for them, I must confess), so difficult to recognise them, and not many acquaintances, you saw them. Simonin looked a dear. The boatswain of the »Peterhof« with the St. George's cross — all well, Shirinsky too looks well. The Commandant is such a nice simple kind, not fussy man. Begged me to send still 3000 Images by our sailors at a fortress-station, they dressed as soldiers, we as nurses, stopped and looked at the feeding station and barracks hospitals at station and service in wee Church. Some heavy cases. The Livland committee — (Pss. Schetvertinskaya at the head, her property is close by), the daugther as nurse. — At 2 we stopped at a station, I discovered a sanitary train and out we flew, climbed into the boxcars. 12 men lying comfortably, drinking tea, by the light of a candle — saw all and gave Images — 400. An ill Priest too was there — »Zemsky« train, 2 sisters (not dressed as such) 2 brothers of mercy, 2 doctors and many sanitaries. I begged pardon for waking them up, they thanked us for coming, were delighted, cheery, smiling and eager faces. So we were an hour late and cought it up in the night, so that I was rocked to and fro, and feared we should capsize.

So now I saw Irina, after which must meet my Sanitary train. Ella arrives to morrow evening. God bless and protect you — no news from you since Friday. Very tenderest, fondest kisses from your very own old wify

Sunny.

Victoria sends love, living Kent House Isle of Wight.

Messages to N. P.

Nicholas's telegrammed reply:

Telegram.

Stanichnaia. 24 November, 1914.

Have spent three happy hours at Ekaterinodar. Thanks for telegram. I remember about Olga. Embrace you all closely.

Nicky.

Above: Nicholas and Alexandra.

Wednesday, May 20, 2020

Alexandra's Fabergé eggs kept in the Maple Room vitrine

Source:

https://www.wintraecken.nl/mieks/faberge/ned/eggs-AF.htm

The eggs (from top to bottom; six can be definitively identified):

The Colonnade egg, 1910:

Fifteenth Anniversary egg, 1911:

The Moscow Kremlin egg, 1906:

The Romanov Tercentenary egg, 1913:

The Alexander Palace egg, 1908:

The Standart egg, 1909:

The Tsarevich egg, 1912:

Photo of the eggs in the vitrine:

The reconstructed vitrine seat (still needs finishing touches):

(photos courtesy of ivankirdeev1986 on Instagram)

https://www.wintraecken.nl/mieks/faberge/ned/eggs-AF.htm

The eggs (from top to bottom; six can be definitively identified):

The Colonnade egg, 1910:

Fifteenth Anniversary egg, 1911:

The Moscow Kremlin egg, 1906:

The Romanov Tercentenary egg, 1913:

The Alexander Palace egg, 1908:

The Standart egg, 1909:

The Tsarevich egg, 1912:

Photo of the eggs in the vitrine:

The reconstructed vitrine seat (still needs finishing touches):

(photos courtesy of ivankirdeev1986 on Instagram)

Tuesday, May 19, 2020

Saturday, May 16, 2020

Some paintings from the Pallisander Room

Sources:

https://goskatalog.ru/portal/#/collections?id=1214900

https://goskatalog.ru/portal/#/collections?id=1214360

https://goskatalog.ru/portal/#/collections?id=21607256

https://goskatalog.ru/portal/#/collections?id=21607254

Above: The Madonna and Child, by Paul Thumann.

Above: The Annunciation, by Susanna Renata Granich.

Above: Portrait of Alexandra's first cousin Helena Victoria, by Kobervein. This portrait is commonly misidentified as depicting Alexandra's mother Alice.

Above: Portrait of Alexei, by Trifonov.

These paintings are shown in these photos of the room:

https://goskatalog.ru/portal/#/collections?id=1214900

https://goskatalog.ru/portal/#/collections?id=1214360

https://goskatalog.ru/portal/#/collections?id=21607256

https://goskatalog.ru/portal/#/collections?id=21607254

Above: The Madonna and Child, by Paul Thumann.

Above: The Annunciation, by Susanna Renata Granich.

Above: Portrait of Alexandra's first cousin Helena Victoria, by Kobervein. This portrait is commonly misidentified as depicting Alexandra's mother Alice.

Above: Portrait of Alexei, by Trifonov.

These paintings are shown in these photos of the room:

Thursday, May 14, 2020

Sunday, May 10, 2020

Alexandra's letters to Nicholas, dated November 21, 1914, and Nicholas's telegrammed reply

Sources:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=inu.30000011396573&view=1up&seq=78

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=inu.30000011396573&view=1up&seq=79

http://www.alexanderpalace.org/letters/november14.html

Alexandra wrote these two letters to Nicholas on November 21, 1914, and he replied with a telegram two days later.

Alexandra's letters:

Tsarskoje Selo, Nov. 21-st 1914

My Lovebird,

I don't want the Feldjeger to leave to-morrow without a letter from me. This is the wire I just received from our Friend. »When you comfort the wounded God makes His name famous through your gentleness and glorious work.« So touching and must give me strength to get over my shyness. — Its sad leaving the wee ones! —

Iza suddenly had 38 and pains in her inside, so Vladimir Nikolaievitch wont let her go. — Fullspeed we telephoned to Nastinka to get ready and come. —

We are taking parcels and letters from all the naval wives for Kovno.

We are eating, and the Children chattering like waterfalls, which makes it somewhat difficult to write. —

Now Light of my life, farewell. God bless and protect you and keep you from all harm. I do not know when and where this letter will reach you. — Blessings without end and fondest kisses from us all. Your very own

Sunny.

We all send messages to N. P. — and Dmitri Sheremetiev.

—

Tsarskoje Selo, Nov. 21-st 1914

My own beloved Treasure,

Its nice that we were together at Smolensk 2 years ago (with C. Keller) so I can imagine where you were. Alexei's »committee« wired to me after you had been there to see them. I remember them giving Baby an Image at that famous tea there. — Still no news of the war through fat Orlov since you left. One whispers that Joachim has been taken by our troops — if so, where has he been sent to, I wonder. If true, one might have let Dona know through Vicky of Sweden that he is safe and sound (not saying where) but you know better, its not for me to advise you, its only a mother pittying another mother. —

I remained at home in the afternoon yesterday, and lay in bed before dinner, being dead-tired. The girls went to the hospital instead of me. After dinner I received Schulenburg rather long; he leaves Saturday again. The bombs were being thrown daily over Varsovie and everywhere and at night. Baby's train stuck an hour and ½ on the bridge (full of wounded, over 600) and could not get into the station (coming from Praga) on account of the other trains, and he feared every minute that they would be blown up. — Then I received Ressin — quick man — in an hour he settled all the plans, and we leave this evening at 9, reach Vilna Saturday morning at 10-15. — Then continue to Kovno 2.50-6, back Tsarskoje Selo Sunday morning at 9. Ressin only lets the Gov. of Vilna know, because of motors or carriages and he is not to tell on — from there he will let the Gov. at Kovno know (or its the same man). Ania has telephoned privately to Rodionov — I hope we may catch a glimpse of them somewhere. — A. is very proud she kept me from going to the hospital as tiring — but its her doing this expedition which is tiring — 2 nights in the train and 2 towns to visit hospitals — if we see the dear sailors, it will be a recompense. — I am glad we can manage it so quickly and wont be long away from the Children. — Excuse this dirty page, but I am quite ramolie and my head is weak, I even asked for a little wine. 100 questions, papers — beginning by Viltchkovsky in the hospital, every morning questions to answer, resolutions to be taken and so on — and my brain is not as strong or fresh as it was before my heart got so bad all these years. I understand what you feel like of a morning when one after the other come bothering you with questions. — At the hospital I received a »Khansha« who gave me M-me Mdivani motors and was going to send an unit for the Caucasian troops on the German frontier — now she asked my permission to change, and have it in the Caucasus where sanitary help is yet more deficient. — I could not get to sleep this night, so at 2 wrote to A. to tell her to let the naval wives know there is an occasion safely to forward letters or packets — then I sorted out booklets, gospels (1 Apostel), prayers to take for the sailors, goodies and sugared fruits for the officers — perhaps shall find still warm things to add. — For your second dear letter, thanks without end. It was a joy to receive it, sweetheart. It is such anguish to think of our tremendous losses; several wounded officers, who left us a month ago, have returned again wounded. Would to God this hideous war could end quicker, but one sees no prospect of it for long. Of course the Austrians are furious being led by Prussians, who knows whether they wont be having stories still amongst each other. — I received letters from Thora, Q. Helena and A. Beatrice, all send you much love and feel for you deeply. They write the same about their wounded and prisoners, the same lies have been told them too. They say the hatred towards England is the greatest. According to the telegrams Georgie is in France seeing his wounded. — Our Friend hopes you wont remain too long away so far. — I send you papers and a letter from Ania. — Perhaps you will mention in your telegram, that you thank for papers and letter and send messages. I hope her letters are not the old oily style again. — Very mild weather. At 9½ we went to the end of mass in the Pestcherny Chapel — then to our hospital where I had heaps to do, the girls nothing and then to an operation in the big hospital. And we showed our officers to Zeidler to ask advice. — Olga and Tatiana went in despair to town to a concert in the Circus for Olga's committee — without her knowledge one had invited all the ministers and Ambassadors, so she was obliged to go.

Mme Zizi, Isa and Nastinka accompanied them, and I asked Georgi to go too and help them, — he at once agreed to go — kind fellow. — I must write still to Olga with the eatables I send her. Her friend has gone there for short, as he is unwell, like Boris with the itch, and needs a good cleaning. — A. says she has looked through the newspaper and its very dull, she begs pardon for sending it, she thought it was a nice one. Just back from the big Palace and dressings I looked at, and sat with officers.

Now Malama comes to tea to say quite goodbye.

Goodbye my Angel huzzy.

God bless and protect you.

1000 fond kisses from your own old

Wify.

The Children all kiss you. We all send heaps of messages to N. P. —

Long for you!

Nicholas's reply telegram:

Telegram.

Kharkov. 23 November, 1914

Sincerest thanks for dear letters. I hope that yesterday's papers have arrived. Have seen numbers of hospitals, but had no time to see the son of Count Keller. The reception was so touching. I am leaving at four o'clock for Ekaterinodar.

Above: Nicholas and Alexandra.

Note: ramolie (should be ramollie) = weakened

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=inu.30000011396573&view=1up&seq=78

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=inu.30000011396573&view=1up&seq=79

http://www.alexanderpalace.org/letters/november14.html

Alexandra wrote these two letters to Nicholas on November 21, 1914, and he replied with a telegram two days later.

Alexandra's letters:

Tsarskoje Selo, Nov. 21-st 1914

My Lovebird,

I don't want the Feldjeger to leave to-morrow without a letter from me. This is the wire I just received from our Friend. »When you comfort the wounded God makes His name famous through your gentleness and glorious work.« So touching and must give me strength to get over my shyness. — Its sad leaving the wee ones! —

Iza suddenly had 38 and pains in her inside, so Vladimir Nikolaievitch wont let her go. — Fullspeed we telephoned to Nastinka to get ready and come. —

We are taking parcels and letters from all the naval wives for Kovno.

We are eating, and the Children chattering like waterfalls, which makes it somewhat difficult to write. —

Now Light of my life, farewell. God bless and protect you and keep you from all harm. I do not know when and where this letter will reach you. — Blessings without end and fondest kisses from us all. Your very own

Sunny.

We all send messages to N. P. — and Dmitri Sheremetiev.

—

Tsarskoje Selo, Nov. 21-st 1914

My own beloved Treasure,

Its nice that we were together at Smolensk 2 years ago (with C. Keller) so I can imagine where you were. Alexei's »committee« wired to me after you had been there to see them. I remember them giving Baby an Image at that famous tea there. — Still no news of the war through fat Orlov since you left. One whispers that Joachim has been taken by our troops — if so, where has he been sent to, I wonder. If true, one might have let Dona know through Vicky of Sweden that he is safe and sound (not saying where) but you know better, its not for me to advise you, its only a mother pittying another mother. —

I remained at home in the afternoon yesterday, and lay in bed before dinner, being dead-tired. The girls went to the hospital instead of me. After dinner I received Schulenburg rather long; he leaves Saturday again. The bombs were being thrown daily over Varsovie and everywhere and at night. Baby's train stuck an hour and ½ on the bridge (full of wounded, over 600) and could not get into the station (coming from Praga) on account of the other trains, and he feared every minute that they would be blown up. — Then I received Ressin — quick man — in an hour he settled all the plans, and we leave this evening at 9, reach Vilna Saturday morning at 10-15. — Then continue to Kovno 2.50-6, back Tsarskoje Selo Sunday morning at 9. Ressin only lets the Gov. of Vilna know, because of motors or carriages and he is not to tell on — from there he will let the Gov. at Kovno know (or its the same man). Ania has telephoned privately to Rodionov — I hope we may catch a glimpse of them somewhere. — A. is very proud she kept me from going to the hospital as tiring — but its her doing this expedition which is tiring — 2 nights in the train and 2 towns to visit hospitals — if we see the dear sailors, it will be a recompense. — I am glad we can manage it so quickly and wont be long away from the Children. — Excuse this dirty page, but I am quite ramolie and my head is weak, I even asked for a little wine. 100 questions, papers — beginning by Viltchkovsky in the hospital, every morning questions to answer, resolutions to be taken and so on — and my brain is not as strong or fresh as it was before my heart got so bad all these years. I understand what you feel like of a morning when one after the other come bothering you with questions. — At the hospital I received a »Khansha« who gave me M-me Mdivani motors and was going to send an unit for the Caucasian troops on the German frontier — now she asked my permission to change, and have it in the Caucasus where sanitary help is yet more deficient. — I could not get to sleep this night, so at 2 wrote to A. to tell her to let the naval wives know there is an occasion safely to forward letters or packets — then I sorted out booklets, gospels (1 Apostel), prayers to take for the sailors, goodies and sugared fruits for the officers — perhaps shall find still warm things to add. — For your second dear letter, thanks without end. It was a joy to receive it, sweetheart. It is such anguish to think of our tremendous losses; several wounded officers, who left us a month ago, have returned again wounded. Would to God this hideous war could end quicker, but one sees no prospect of it for long. Of course the Austrians are furious being led by Prussians, who knows whether they wont be having stories still amongst each other. — I received letters from Thora, Q. Helena and A. Beatrice, all send you much love and feel for you deeply. They write the same about their wounded and prisoners, the same lies have been told them too. They say the hatred towards England is the greatest. According to the telegrams Georgie is in France seeing his wounded. — Our Friend hopes you wont remain too long away so far. — I send you papers and a letter from Ania. — Perhaps you will mention in your telegram, that you thank for papers and letter and send messages. I hope her letters are not the old oily style again. — Very mild weather. At 9½ we went to the end of mass in the Pestcherny Chapel — then to our hospital where I had heaps to do, the girls nothing and then to an operation in the big hospital. And we showed our officers to Zeidler to ask advice. — Olga and Tatiana went in despair to town to a concert in the Circus for Olga's committee — without her knowledge one had invited all the ministers and Ambassadors, so she was obliged to go.

Mme Zizi, Isa and Nastinka accompanied them, and I asked Georgi to go too and help them, — he at once agreed to go — kind fellow. — I must write still to Olga with the eatables I send her. Her friend has gone there for short, as he is unwell, like Boris with the itch, and needs a good cleaning. — A. says she has looked through the newspaper and its very dull, she begs pardon for sending it, she thought it was a nice one. Just back from the big Palace and dressings I looked at, and sat with officers.

Now Malama comes to tea to say quite goodbye.

Goodbye my Angel huzzy.

God bless and protect you.

1000 fond kisses from your own old

Wify.

The Children all kiss you. We all send heaps of messages to N. P. —

Long for you!

Nicholas's reply telegram:

Telegram.

Kharkov. 23 November, 1914

Sincerest thanks for dear letters. I hope that yesterday's papers have arrived. Have seen numbers of hospitals, but had no time to see the son of Count Keller. The reception was so touching. I am leaving at four o'clock for Ekaterinodar.

Above: Nicholas and Alexandra.

Note: ramolie (should be ramollie) = weakened

Elisabeth's postcard for Nicholas and Alexandra, New Year 1894/1895

Source:

romanovsonelastdance on Tumblr

https://romanovsonelastdance.tumblr.com/post/145098868625/card-from-elizaveta-feodorovna-to-nicholas-ii-and

The postcard:

For both dears!

The Sun!

the flowers!

love without end

& blessings for new year.

Ella

1894-95

Above: Elisabeth.

Above: Nicholas and Alexandra.

romanovsonelastdance on Tumblr

https://romanovsonelastdance.tumblr.com/post/145098868625/card-from-elizaveta-feodorovna-to-nicholas-ii-and

The postcard:

For both dears!

The Sun!

the flowers!

love without end

& blessings for new year.

Ella

1894-95

Above: Elisabeth.

Above: Nicholas and Alexandra.

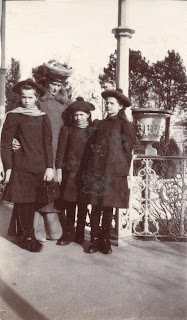

Alexandra and her children

In honour of Mother's Day, here are some photos of Alexandra with her children over the years.

1896:

1897:

1898:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1899:

1900:

1901:

1902:

(photo courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1904:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1905:

(photos courtesy of White Grand Duchess on VK)

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1906:

(photos courtesy of White Grand Duchess on VK)

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1907:

(photos courtesy of White Grand Duchess on VK)

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1908:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1909:

(photos courtesy of White Grand Duchess on VK)

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1910:

(photo courtesy of White Grand Duchess on VK)

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1911:

(photo courtesy of White Grand Duchess on VK)

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1912:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1913:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1914:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1915:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1916:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1917:

1918:

1896:

1897:

1898:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1899:

1900:

1901:

1902:

(photo courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1904:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1905:

(photos courtesy of White Grand Duchess on VK)

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1906:

(photos courtesy of White Grand Duchess on VK)

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1907:

(photos courtesy of White Grand Duchess on VK)

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1908:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1909:

(photos courtesy of White Grand Duchess on VK)

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1910:

(photo courtesy of White Grand Duchess on VK)

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1911:

(photo courtesy of White Grand Duchess on VK)

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1912:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1913:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1914:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1915:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1916:

(photos courtesy of lastromanovs on VK)

1917:

1918:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)