Sources:

Treize années à la cour de Russie: Le tragique destin de Nicolas II et de sa famille, pages 81 to 86, by Pierre Gilliard, 1921

Thirteen Years at the Russian Court, pages 98 to 106, by Pierre Gilliard, translated by F. Appelby Holt, 1921

The account:

Le [20 juillet] après-midi le président de la République arrivait sur le cuirassé La France en rade de Cronstadt où l'empereur était venu l'attendre. Ils rentrèrent ensemble à Péterhof et M. Poincaré fut conduit dans les appartements au Grand Palais. Le soir un dîner de gala fut donné en son honneur, l'impératrice et les dames de sa suite y assistèrent.

Le président de la République fut pendant quatre jours l'hôte de Nicolas II et de nombreuses solennités marquèrent son court séjour. L'impression qu'il fît sur l'empereur fut excellente et j'eus personellement l'occasion de m'en convaincre dans les circonstances suivantes.

M. Poincaré avait été invité à prendre part au déjeuner de la famille impériale, dont il était le seul convive. On le reçut sans le moindre apparat au petit cottage d'Alexandria, dans le cadre intime de la vie de tous les jours. ...

Le 23 juillet, après un dîner d'adieu offert à Leurs Majestés sur La France, le président quittait Cronstadt à destination de Stockholm.

Le lendemain nous apprenions avec stupeur que l'Autriche avait remis la veille au soir un ultimatum à la Serbie. Je rencontrai l'après-midi l'empereur dans le parc, il était préoccupé, mais ne semblait pas inquiet.

Le 25, un Conseil extraordinaire est réuni à Krasnoïé-Sélo sous la présidence de l'empereur. On décide d'observer une politique de conciliation, digne et ferme toutefois. Les journaux commentent avec passion la démarche de l'Autriche.

Les jours suivants, le ton de la presse devient de plus en plus violent. On accuse l'Autriche de vouloir écraser la Serbie. La Russie ne peut laisser anéantir la petite nation slave. Elle ne peut tolérer la suprématie austro-allemande dans les Balkans. L'honneur national est en jeu.

Cependant, tandis que les esprits s'échauffent, et que la diplomatie met en branle tous les rouages de ses chancelleries, des télégrammes angoissés partent du cottage d'Alexandria pour la lointaine Sibérie où Raspoutine se remet lentement de sa blessure à l'hôpital de Tioumen. Ils sont tous à peu près la même teneur: «Nous sommes effrayés par la perspective de la guerre. Crois-tu qu'elle soit possible? Prie pour nous. Soutiens-nous de tes conseils.» Et Raspoutine de répondre qu'il faut éviter la guerre à tout prix si l'on ne veut pas attirer les pires calamités sur la dynastie et sur le pays tout entier. Ces conseils répondaient bien au vœu intime de l'empereur dont les intentions pacifiques ne sauraient être mises en doute. Il faut l'avoir vu pendant cette terrible semaine de la fin de juillet pour comprendre par quelles angoisses et quelles tortures morales il a passé. Mais le moment était venu où l'ambition et la perfidie germaniques devaient avoir raison de ses dernières hésitations et allaient tout entraîner dans la tourmente.

Malgré toutes les offres de médiation, et bien que le gouvernement russe eût proposé de liquider l'incident par un entretien direct entre Saint-Pétersbourg et Vienne, nous apprenions le 29 juillet que la mobilisation générale avait été ordonnée en Autriche. Le lendemain c'était la nouvelle du bombardement de Belgrade et le surlendemain la Russie répondait par la mobilisation de toute son armée. Le soir de ce même jour, le comte de Portalès, ambassadeur d'Allemagne à Saint-Pétersbourg, venait déclarer à Sazonof que son gouvernement donnait un délai de douze heures à la Russie pour arrêter la mobilisation, faute de quoi l'Allemagne mobiliserait à son tour.

Le délai accordé par l'ultimatum à la Russie expirait le samedi, 1er août, à midi. Le comte de Portalès ne parut cependant que le soir au ministère des affaires étrangères. Introduit chez Sazonof, il lui remit solennellement la déclaration de guerre de l'Allemagne à la Russie. Il était 7 heures 10; l'acte irréparable venait de s'accomplir.

...

Au moment où cette scène historique se déroulait dans le cabinet du ministre des affaires étrangères à Saint-Pétersbourg, l'empereur, l'impératrice et leurs filles assistaient à l'office du soir dans la petite église d'Alexandria. En rencontrant l'empereur quelque heures plus tôt, j'avais été frappé de son expression de grande lassitude: il avait les traits tirés, le teint terreux, et les petites poches qui se formaient sous ses yeux quand il était fatigué semblaient avoir démesurément grandi. Et maintenant il priait de toute son âme pour que Dieu écartât de son peuple cette guerre qu'il sentait déjà toute proche et presque inévitable. Tout son être semblait tendu dans un élan de sa foi simple et confiante. A côté de lui, l'impératrice, dont le visage douloureux avait l'expression de grande souffrance que je lui avais vue si souvent au chevet d'Alexis Nicolaïévitch. Elle aussi priait ce soir-là avec une ferveur ardente, comme pour conjurer la menace redoutable...

Le service religieux terminé, Leurs Majestés et les grandes-duchesses rentrèrent au cottage d'Alexandria; il était près de huit heures. L'empereur, avant de se rendre à table, passa dans son cabinet de travail pour prendre connaissance des dépêches qui avaient été apportées en son absence, et c'est ainsi qu'il apprit, par un message de Sazonof, la déclaration de guerre de l'Allemagne. Il eut un court entretien par téléphone avec son ministre et le pria de venir le rejoindre à Alexandria dès qu'il en aurait la possibilité.

Cependant l'impératrice et les grandes-duchesses attendaient à la salle à manger. Sa Majesté, inquiète de ce long retard, venait de prier Tatiana Nicolaïevna d'aller chercher son père, lorsque l'empereur, très pâle, apparut enfin et leur annonça, d'une voix qui malgré lui trahissait son émotion, que la guerre était déclarée. A cette nouvelle l'impératrice se mit à pleurer et les grandes-duchesses, voyant la désolation de leur mère, fondirent en larmes à leur tour. ...

English translation (by Holt):

In the afternoon of [the 20th of July] the cruiser La France arrived in Cronstadt harbour with the French President on board. The Czar was there to receive him. They returned to Peterhof together, and M. Poincaré was taken to the apartments prepared for him in the palace. In the evening a gala banquet was given in his honour, and the Czarina and the ladies-in-waiting were present.

For four days the President of the French Republic was the guest of Nicholas II., and many ceremonies marked his short visit. He made an excellent impression upon the Czar, a fact which I was able to prove to my own satisfaction under the following circumstances.

M. Poincaré had been invited to the Imperial luncheon-table, where he was the sole guest. He was received without the slightest formality into the family circle at the little Alexandria Cottage. ...

On July 23rd the President left Cronstadt for Stockholm, immediately after a dinner given in Their Majesties' honour on the La France.

The next day, to our utter amazement, we learned that Austria had presented an ultimatum to Serbia on the previous evening. I met the Czar in the park in the afternoon. He was preoccupied, but did not seem anxious.

On the 25th an Extraordinary Council was held at Krasnoïe-Selo in the Czar's presence. It was decided to pursue a policy of dignified but firm conciliation. The Press was extremely angry at the step taken by Austria.

The next few days the tone of the Press became increasingly violent. Austria was accused of desiring to annihilate Serbia. Russia could not let the little Slav state be overwhelmed. She could not tolerate an Austro-Hungarian supremacy in the Balkans. The national honour was at stake.

Yet while tempers were rising and the diplomats were setting the machinery of all the chancellories in motion, heart-rending telegrams left Alexandria Cottage for distant Siberia, where Rasputin was slowly recovering from his wound in the hospital at Tioumen. They were nearly all of the same tenor: "We are horrified at the prospect of war. Do you think it is possible? Pray for us. Help us with your counsel."

Rasputin would reply that war must be avoided at any cost if the worst calamities were not to overtake the dynasty and the Empire.

This advice was consonant with the dearest wish of the Czar, whose pacific intentions could not be doubted for a moment. We had only to see him during that terrible last week of July to realise what mental and moral torture he had passed through. But the moment had come when the ambition and perfidy of Germany were to steel him against his own last hesitation and sweep everything with them into the whirlpool.

In spite of all the offers of mediation and the fact that the Russian Government had suggested closing the incident by direct negotiations between St. Petersburg and Vienna, we learned on July 29th that general mobilisation had been ordered in Austria. The next day we heard of the bombardment of Belgrade, and on the following day Russia replied with the mobilisation of her whole army. In the evening of that day Count Portalès, the German Ambassador at St. Petersburg, called to inform M. Sazonoff that his Government would give Russia twelve hours in which to stop her mobilisation, failing which Germany would mobilise in turn.

The twelve hours granted to Russia in the ultimatum expired at noon on Saturday, August 1st. Count Portalès, however, did not appear at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs until the evening. He was shown into Sazonoff, and then formally handed him Germany's declaration of war on Russia. It was ten minutes past seven. The irreparable step had been taken.

...

At the moment when this historic scene was taking place in the Foreign Minister's room at St. Petersburg, the Czar, the Czarina, and their daughters were attending evensong in the little Alexandria church. I had met the Czar a few hours before, and been much struck by the air of weary exhaustion he wore. The pouches which always appeared under his eyes when he was tired seemed to be markedly larger. He was now praying with all the fervour of his nature that God would avert the war which he felt was imminent and all but inevitable.

His whole being seemed to go out in an expression of simple and confident faith. At his side was the Czarina, whose care-worn face wore that look of suffering I had so often seen at her son's bedside. She too was praying fervently that night, as if she wished to banish an evil dream. ...

When the service was over Their Majesties and the Grand-Duchesses returned to Alexandria Cottage. It was almost eight o'clock. Before the Czar came down to dinner he went into his study to read the dispatches which had been brought in his absence. It was thus, from a message from Sazonoff, that he learned of Germany's declaration of war. He spoke to his Minister on the telephone for a short time and asked him to come down to Alexandria Cottage the moment he could get away.

Meanwhile the Czarina and the Grand-Duchesses were waiting for him in the dining-room. Her Majesty, becoming uneasy at the long delay, had just asked Tatiana Nicolaïevna to fetch her father, when the Czar appeared, looking very pale, and told them that war was declared, in a voice which betrayed his agitation, notwithstanding all his efforts. On learning the news the Czarina began to weep, and the Grand-Duchesses likewise dissolved into tears on seeing their mother's distress. ...

Above: Alexandra.

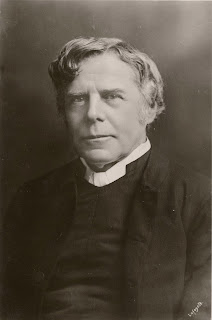

Above: Pierre Gilliard.