Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia (1872-1918) was the wife of Russia's last Tsar, Nicholas II (1868-1918) and thereby she was Empress of Russia from their marriage on November 26, 1894 until Nicholas' forced abdication on March 2, 1917. They and their five children were brutally murdered in a Siberian cellar in the early hours of July 17, 1918.

Above: Alexandra in Russian court dress, year 1908.

Alexandra was born Princess Alix Victoria Helena Louise Beatrice of Hesse-Darmstadt or Hesse and by Rhine on June 6, 1872 at the New Palace in the Grand Duchy of Hesse in Germany. Her parents were Grand Duke Louis of Hesse (1837-1892) and Grand Duchess Alice, born Princess Alice of the United Kingdom (1843-1878), making Alix a granddaughter of Queen Victoria (1819-1901). She was named Alix because her mother felt that the German people mispronounced her name, so when her new daughter was born, she was given the closest German rendering of the name Alice. Alix had two older brothers, Ernst (1868-1937) and Friedrich (1870-1873), and three older sisters, Victoria (1863-1950), Elisabeth (1864-1918) and Irene (1866-1953).

Above: Alix as a baby, year 1872.

Above: The New Palace, where Alix was born. It was damaged in a bombing raid during World War Two and demolished in 1955.

Above: Alix as a toddler.

Above: Alix as a toddler.

Alix as a baby was considered to be very pretty, with a resemblance to Elisabeth, "always smiling and with a dimple in one cheek", wrote Alice in a letter. The little girl was indeed always happy and smiling, and her family nicknamed her "Sunny" for her cheerful nature, a nickname Nicholas would one day also come to use for her. Alix was one of Queen Victoria's favourite grandchildren, and was described by her as "the handsomest child I ever saw."

Despite her German birth, Alix's first language was English, and her upbringing was surprisingly simple for a royal child: importance was given to being dutiful, humble and polite, going out for long walks, pony rides and fresh air regardless of the weather. Alix and her siblings were not spoiled: they were taught to make their beds themselves and to look down on idleness and keep themselves busy with things like needlework, letter-writing, knitting, etc.

Above: Alix as a child.

Above: Alix as a child.

Above: Alix as a child.

Above: Alix as a child.

On May 24, 1874, the family welcomed another little girl: Marie Victoria Feodore Leopoldine, often nicknamed May. As she was the closest sister to Alix in age, the two shared a close bond and were each other's favourite playmates.

Above: Princess Marie as a baby.

Above: Alix with Irene, Ernst and Marie, year 1876.

Above: Princess Marie, nicknamed May.

Above: The Hesse family, year 1875.

Above: Alix and May in 1878, just months before May's tragic death.

"The Princesses Victoria and Ella (Elizabeth) were already in the schoolroom when their sister was born, and Princess Irene was by herself, between nursery and schoolroom. Princess Alix's babyhood was thus spent mostly with her brother and Princess May. This beloved elder brother, the originator of all their games, was the object of her deep admiration, and the intimacy of childhood remained with them all their lives.

Life in both nursery and schoolroom followed definite rules, laid down by the children's mother, and on the same simple lines as those on which Queen Victoria's children had been brought up. ... Their children were brought up in accordance with old-fashioned English ideals of hygiene, which were, at that time, far ahead of those in Germany. Their dress was simple and their fare of the plainest; indeed they kept all their lives hated memories of rice puddings and baked apples in endless succession.

The nurseries were large, lofty rooms, very plainly furnished. Mrs. Mary Anne Orchard, 'Orchie' to the children, ruled the nursery. She was the ideal head nurse, sensible, quiet, enforcing obedience, not disdaining punishment, but kind though firm. She gave the children that excellent nursery training which leaves a stamp for life. Mrs. Orchard had fixed hours for everything; and the children's day was strictly divided in such a way as to allow them to take advantage of every hour that their mother could spare for them.

On the same floor as the nurseries were the Grand Duchess's rooms, and there the little Princesses brought their toys and played while their mother wrote or read. Toys were simple in those days compared with the elaborate ones that modern children have. Princess Alix never cared for dolls; they were not 'real' enough, she preferred animals that responded to caresses, and she delighted in games. Sometimes all the old boxes containing their mother's early wardrobe were brought out for dressing up. The children strutted down the long corridors in crinolines, and played at being great ladies, or characters from fairy tales, dressed in bright stuffs and Indian shawls, which their grandmother, Queen Victoria, could not have imagined being put to such a use. The Grand Duke was not able to be much with his children, but their rare games with him were a delight, and Princess Alix's earliest recollections were of romps in which their big burly soldier father joined.

The children were full of fun and mischief. They did not always drive decorously in their small pony carriage, with a liveried footman at the pony's head. They sometimes escaped from their nurse's vigilance, and once Princess Alix paid dearly for such an escapade. The children were staying at Darmstadt just after their mother's death and were chasing one another in the garden. Princess Irene and Prince Ernest ran over some high forcing frames, carefully treading only on the stone. Princess Alix — who was six at the time — followed, but tried to run over the glass panes. She crashed through, and was badly cut by the glass, beating on her legs the scars of this adventure all her life.

Winters were spent at Darmstadt, summers mostly at the castles of Kranichstein or Seeheim. It is easy to picture the band of merry, high-spirited children romping in the suites of old-fashioned rooms at Kranichstein, racing in the park under the oaks, standing in deep admiration before the ancient winding staircase on which the picture of a lifesized stag commemorated the spot where a real stag once sought refuge from a Landgrave of old days. Christmas was celebrated partly in the English and partly in the German way, and was a family feast in which all the household shared. A huge Christmas tree stood in the ballroom, its brances laden with candles, apples, gilt nuts, pink quince sausages, and all kinds of treasures. Round it were tables with gifts for all the members of the family. The servants came in and the Grand Duchess gave them their presents. Then followed a family Christmas dinner, at which the traditional German goose was followed by real English plum pudding and mince pies sent from England. The poor were not forgotten, and Princess Alice had gifts sent to all the hospitals. Later, the Empress continued the same Christmas customs in Russia.

Every year, much to the children's delight, the whole family went to England, staying at Windsor Castle, Osborne or Balmoral, according to Queen Victoria's residence at the moment. The Queen was adored by all her grandchildren. She was always a fond grandmother, and did not apply to them the strict rules that had governed her own children.

In England the little Prince and Princesses of Hesse met crowds of cousins, including the children of the Prince and Princess of Wales (King Edward VII) and those of Princess Christian. With this merry band, they played about Windsor, wandered in the grounds at Balmoral and Osborne, visited pet little shops and had their own special friends among the Queen's retainers. They went round to see these old friends every time they came over, and the visit to 'the merchants', by which name a small shop between Abergeldie and Balmoral was known to them, was never missed.

The 'merchants' sold sweets, notepaper, and other small things, and the children would come back from their expedition, laden with wonderful purchases, to which the kindly 'merchants', an old lady and her sister, would generally add a sweet something. The great delight of the young Princesses at being initiated by their old friend and her sister into the secrets of scone-baking was remembered all their lives, and the tales of these adventures, recounted in later days, filled the hearts of the Imperial Russian children with longing envy. 'Grandmamma in England' was, to the childish imagination of Princess Alix, a combination of a very august person and of a Santa Claus. When she returned from England Princess Alix would talk about her stay for weeks and would begin to look forward to the next year's visit.

During the winter at Darmstadt, Princess Alice would often take her children with her to hospitals and charitable institutions. They thus learned from an early age to enjoy giving pleasure to others, and Princess Alix, when quite tiny, would take flowers to hospitals on her mother's behalf.

Occasionally other children came to play with the small Princesses at Darmstadt, and there were children's parties, but these Princess Alix did not much enjoy. Her constitutional shyness was beginning to show itself, and she always kept in the background.

The friend of her babyhood, who remained her most intimate companion till her marriage, was Fraulein Toni Becker. She and Toni played together as babies, and later shared dancing and gymnastic lessons. As they grew older, their intimacy grew also, till, when Princess Alix came out, Toni was at the Palace almost every day.

In 1877, the death of his uncle, the Grand Duke Louis, made Princess Alix's father reigning Grand Duke of Hesse. This event produced no change in the children's lives, but for the Grand Duchess Alice it meant a great increase of public duties, and consequently a considerable strain on her health. In the summer of 1878 she was ordered to Eastbourne, and took all her children with her, going thence on a short visit to Queen Victoria. Of Eastbourne Princess Alix had golden memories of crab-fishing, bathing, and sand-castle building. There were, too, delightful games with other children on the beach, for many of the Grand Duchess Alice's friends were there with children of about the same age as hers." - from

The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna, written by Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden

Sadly, Alix's happy, idyllic childhood did not last long. In November 1878, a diphtheria epidemic swept through the palace, and all of the children except Elisabeth fell ill with the disease. Alice nursed them herself, but despite her efforts, little May died on November 16th at the age of four, and on December 14, Alice died at age 35 after contracting the illness herself. The double tragedy and loss of her beloved mother at such a young age traumatised the six year old Alix and utterly transformed her personality. She rarely smiled or laughed anymore and became almost always very introverted and serious. She grew deeply religious, very shy, extremely anxious and deeply sensitive, aloof and distrustful of strangers, she gained a pessimistic and fatalistic outlook on life, and she took life itself very seriously. Her deep religiosity, her intense, extreme shyness and social anxiety, deep interest in and sympathy for human suffering, and melancholy air would come to define Alix's character for the rest of her life, and although it was normal and even a bit of an ideal in the Victorian era, she was considered by some to be too melancholy, too introspective and too serious. It was only when in the company of her closest family, friends and relatives or when engaged in charity and nursing work that she would go back to being the cheerful, social, extroverted, smiling "Sunny" of her childhood.

"Princess Alix used to say, in after years, that her earliest recollections were of an unclouded, happy babyhood, of perpetual sunshine, then of a great cloud... The Grand Duchess Alice's death left an inexpressible void in the Palace. It took a long time before those in it could adjust themselves to a life which had lost the hand that guided it. The Grand Duke Louis IV had scarcely recovered from his own severe illness at the time of his wife's death. All the children were moved as soon as possible into the cold, unfamiliar surroundings of the old town-Schloss, and from its windows poor little Princess Alix, then barely six, saw her mother's funeral procession wending its way from the New Palace to the family mausoleum at the Rosenhohe.

The Grand Duke did all in his power to take his wife's place with his motherless children. He was a kind-hearted, honest man, with a wonderfully fair outlook on things and events, and was adored by his children. Naturally he spoiled the youngest a little: Princess Alix seemed so lonely and desolate without her small playfellow, Princess May. ...

The first months after her mother's death were untold misery and loneliness for Princess Alix, and probably laid the foundations of the seriousness that lay at the bottom of her character. She was now quite alone in the nursery. Even Prince Ernest Louis, who was now ten, had a tutor to keep him at lessons all day, and Princess Irene, who was six years older, had joined the elder Princesses in the schoolroom. Princess Alix long afterwards remembered those deadly sad months when, small and lonely, she sat with old 'Orchie' in the nursery, trying to play with new and unfamiliar toys (all her old ones were burned or being disinfected). When she looked up, she saw her old nurse silently crying. ...

Until this time Princess Alix had been on the whole a merry child. She was hot-tempered and ardently desired things, though she showed great self-restraint even at an early age. She was generous, and even in her babyhood incapable of any childish falsehood. She had a warm and loving heart; was obstinate and very sensitive. A chance word could hurt her, but, even as a small girl, she did not show how deeply she had been wounded. This was her childhood's character, and in many traits it shows the future woman." - from

The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna, written by Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden

"Took a short drive with Beatrice, Louis & Alicky, who looked very sweet in her long cloak. I feel a constant returning pang, in looking at this lovely little child, thinking that her darling mother, who so doted on her, was no longer here on earth to watch over her." - Queen Victoria, February 2, 1879

"The Empress told me that when she cried at the marriage of her brother her tears were said to be tears of jealous rage at seeing herself dispossessed of authority. 'But, Lili, I was not jealous. I cried when I thought of my mother; this was the first festival since her death. I seemed to see her everywhere.'" - from

The Real Tsaritsa (1922), written by Lili Dehn

Above: The surviving Hesse sisters in mourning for their mother, year 1879.

Above: The Hesse sisters in mourning with their grandmother, Queen Victoria, year 1879.

Above: Alix in mourning for her mother.

In the wake of Alice's death, three foster mothers entered the scene: Queen Victoria herself and Alix's governesses Mrs. Orchard (known to Alix as "Orchie) and Madgie Jackson ("Mrs. Jackson"). Alix and her surviving family visited Queen Victoria every autumn, sometimes at Osborne House or her other residences, Windsor Castle and Balmoral Castle. She supervised Alix's education and received regular progress reports from her tutors. Alix's practically growing up in England at her grandmother's court ensured that she was instilled with plain, English tastes and strict Victorian morals. Although she played piano beautifully, she found it unbearable and torturous to play for an audience, and she preferred the quiet beauty and peaceful atmosphere of nature and the outdoors over court society with too much noise, too many faces and too much stimulation.

"As the youngest and most vulnerable of the Hesse children, Alix was the Queen's favourite. Grandmother and granddaughter always adored each other. As Empress, the only time when Alix was seen to weep in public was at the memorial service for Queen Victoria at the English church in Petersburg. Lili Dehn, who knew Alix very well, believed that she owed a good deal to Victoria's influence." - from Nicholas II, by Dominic Lieven

"The Grand Ducal family went that first year to Schloss Wolfsgarten, and the new surroundings and the elasticity of youth helped the children to recover their vitality. They returned to the New Palace in the winter of 1879-1880, and Princess Alix began her solitary schoolroom life. She had toiled at her spelling under faithful Orchie's eye; now came the somewhat formidable Fraulein Anna Textor, a connection of Goethe himself, who, under Miss Jackson's general guidance, carried on her education.

Miss Margaret Hardcastle Jackson, 'Madgie' as the Princess Alix affectionately called her later, was a broadminded, cultivated woman, who soon gained a strong influence over her pupils. ... She had impressed the Grand Duchess Alice by her advanced ideas on feminine education. She tried not only to impart knowledge to her pupils, but to form their moral characters and widen their views on life. A keen politician, she was always deeply interested in all important political and social questions of the day. Young as they were, Miss Jackson discussed all such matters with the children, awakening their interest in intellectual questions. Gossip of any kind was not allowed by her. ... It was unfortunate that Miss Jackson felt too old and tired, and had to retire before having quite finished the Princess Alix's education, when her youngest charge was only fifteen, as she would certainly have been able to accustom her to break through her reserve and acquire a simpler and easier outlook on life.

With the thoroughness that ever characterized her, Princess Alix gave her whole energy to her lessons. She always had a strong sense of duty, and her teachers certify that she would always willingly give up any pleasure that she thought might prevent her finishing some task for next day. Samples of her handwriting at seven years old show it to be wonderfully neat and firm, and she had a very retentive memory. By the time she was fifteen, she was well grounded in history, literature, geography and all general subjects, particularly those relating to England and Germany. According to her letters to her eldest sister, she toiled without a murmur at dry works like Guizot's Reformation de la Litterature, the Life of Cromwell and Raumer's Geschichte der Hohenstaufen in nine volumes: compared with these, Paradise Lost, which she had read in the intervals, must have seemed quite light reading! She had a French teacher, and though her accent was fair, she never became thoroughly at home in that language and always felt 'cramped', as she said, in it, being at a loss for words. This hampered her later in Russia, where French was the official language at Court. English was, of course, her natural language. She spoke and wrote it to her brother and sisters, and later to her husband and children and to all those she knew well.

Princess Alix had one of those sensitive natures that respond most readily to music. She 'adored' Wagner and the classics, and when she grew up attended every concert within her reach. Her music teacher was a Dutchman, W. de Haan, at that time Director of the Opera at Darmstadt, who greatly praised her musical ability.

She played the piano brilliantly, but her shyness made her extremely self-conscious whenever she played before people. She told the author of the torment she endured when Queen Victoria made her play in the presence of her guests and suite at Windsor. She said her clammy hands felt literally glued to the keys and that it was one of the worst ordeals of her life. She did not excel in drawing, but was a good needlewoman and designed attractive trifles, which she gave to her friends or to charity bazaars. Her interest in art in general developed later under her brother's influence.

The Grand Duke Louis IV was much with his children, and in summer liked to take them about with him to functions in different towns, or to manouvres. Princess Alix had a very great love for her father, and her delight knew no bounds when she was included in these expeditions. She loved her picturesque 'Hessenland'. She cherished recollections of her childhood and early youth, and always in her mind separated Hesse completely from the rest of Germany, which she looked on as Prussia and as a different country. She went to Berlin only twice on short visits before her marriage.

Nearly every autumn the Grand Duke of Hesse took his children to Windsor or Osborne, or more often, to Balmoral, for he was a keen sportsman and good shot. These visits were the best part of the year to his youngest daughter. They developed her mentally, too, as they brought her into contact not only with her cousins, but with all the Queen's entourage, politicians and notabilities of all sorts. Listening to their conversation at luncheon, her interest in matters beyond her years was unconsciously awakened, and at thirteen Princess Alice looked and spoke like a much older girl. Her English point of view on many questions in later life was certainly due to her many visits to England at this most impressionable age." - from

The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna, written by Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden

Above: Alix, early 1880s.

Above: Alix (at the far right) with her sisters, early 1880s.

Above: Osborne House. Photo courtesy of Anthony McCallum via Wikimedia Commons.

Above: Windsor Castle. It is still used by the British royal family today. Photo taken by Diego Delso.

Above: Balmoral Castle in Scotland. It is still used by the British royal family today. Photo courtesy of Stuart Yeates via Wikimedia Commons.

Above: Alix as a young girl, early 1880s.

Above: Nicholas as a teenager, year 1880.

Above: Ella in 1885, the year of her marriage.

Above: Ella with her husband, the Grand Duke Serge, who would be assassinated in 1905.

Above: The Winter Palace. Photo courtesy of Florstein via Wikimedia Commons.

Above: The Grand Church of the Winter Palace, where Ella and Serge's wedding took place in 1885, and where Nicholas and Alix first met. They too would be wed here nine years later. Photo taken by Januarius-zick.

In 1884, Elisabeth married Grand Duke Serge of Russia, and 12 year old Alix made her first trip to Russia. Their wedding took place in the chapel of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. It was there that Alix first met the 16 year old Tsarevich Nicholas Alexandrovich Romanov, who fell in love with her as soon as he saw her, and within a few years, after seeing Alix again when her father took her on a six-week trip to Russia in 1889, Nicky, as she called him, made it his mission to marry her, although his parents, Tsar Alexander III and his Danish-born wife, Empress Marie Feodorovna, were against the match due to their anti-German views. Marrying the future Tsar of Russia meant that the bride would have to convert to Russian Orthodoxy and take a new Russian name. But the now 17 year old Alix had been confirmed into the Lutheran faith, and she, with her strong sense of virtue, felt overwhelmed and tormented at the idea of converting, despite the fact that she was deeply in love with Nicholas.

"In the spring of 1888 came a great turning-point in Princess Alix's life, her confirmation. She was prepared for this by Dr. Sell, a Hessian divine, chosen by the Grand Duchess Alice to give religious instruction to her children. He was a clever man, who soon gained a strong influence over Princess Alix, whose sensitive soul had always had serious leanings. His early teaching laid the foundations of that searching for 'truth' which was the keynote of her spiritual life. He dwelt strongly on the force of the Lutheran doctrine, and impressed its tenets on her. This later on caused Princess Alix to have so great a moral struggle, when, loving the Tsarevich, and knowing that she was loved by him, she also knew that to marry him she had to embrace the Orthodox faith.

Dr. Sell's words fell deep. Princess Alix's nature was always introspective, and now she began to analyse every action and its right and wrong motive, finding fault with herself, and seeking to attain a lofty and abstract ideal. This made her take her whole life very seriously. She was always mentally fighting things out, always striving to solve deeper questions in connection with small ones, while jealously keeping all this inner life from prying eyes." - from

The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna, written by Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden

"You know what my feelings are as Ella has told them to you already, but I feel it my duty to tell them to you myself. I thought everything for a long time, and I only beg you not to think that I take it lightly for it grieves me terribly and makes me very unhappy.

I have tried to look at it in every light that is possible, but I always return to one thing. I cannot do it against my conscience. You, dear Nicky, who have also such a strong belief will understand me that I think it is a sin to change my belief, and I should be miserable all the days of my life, knowing that I had done a wrongful thing.

I am certain that you would not wish me to change against my conviction. What happiness can come from a marriage which begins without the real blessing of God? For I feel it a sin to change that belief in which I have been brought up and which I love. I should never find my peace of mind again, and like that I should never be your real companion who should help you on in life; for there always should be something between us two, in my not having the real conviction of the belief I had taken, and in the regret for the one I had left.

It would be acting a lie to you, your Religion and to God. This is my feeling of right and wrong, and one's innermost religious convictions and one's peace of conscience toward God before all one's earthly wishes. As all these years have not made it possible to change my resolution in acting thus, I feel that now is the moment to tell you again that I can never change my confession." - Alix in a letter to Nicholas, dated November 8, 1893

Her adamancy caused herself and Nicky to briefly drift away, although they continued to write letters. Alix had suffered another trauma in 1892, when her father died a few days after suddenly having a heart attack; and the loss caused her to have a nervous breakdown, but she inevitably sought comfort in her Nicky throughout that year and the next. Eventually the young lovers reconciled, and during a stay in Coburg in late April 1894, they were engaged.

"In the beginning of 1892 the Grand Duke had slight heart trouble, which was not considered serious. He had a sudden seizure, however, while lunching with his family, and though for nine days his strong frame battled with death, he died on March 13th, 1892, without ever recovering consciousness. His death was a terrible blow to Princess Alix. She watched him day and night, longing for a sign of recognition, for a last word to remember — but in vain. That sad time and the impression of sudden death were always vivid in her memory. She once said to the author, thinking of her father: 'Death is dreadful without preparation, and without the body gradually loosening all earthly ties.'

Her father’s death was perhaps the greatest sorrow of Princess Alix's life. For years she could not speak of him, and long after, when she was in Russia, anything that reminded her of him would bring her to the verge of tears. After his death her sisters stayed at Darmstadt long enough to help her readjust her life. Her brother was now the reigning Grand Duke Ernest Louis. It was to him that she gave all the love she had before divided between father and brother." - from

The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna (1928), written by Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden

"Dear Alicky's grief, Orchard said was terrible, for it was a silent grief, which she locked up within her." - Queen Victoria, April 27th, 1892

"The day after our arrival here, I had a long and extremely difficult conversation with Alix, during which I tried to explain to her that she could not do otherwise than to give her consent! She was crying the whole time, and only answered from time to time in a whisper: ‘No, I cannot!’ I just kept on repeating and insisting on what I had already said earlier. Although this conversation went on for more than two hours, it ended in nothing, because neither of us would give in to the other.

The next morning we talked more calmly; I gave her your letter and after that she could not say anything. This was already a sign for me of the final stage of conflict which had arisen within her from our first conversation. The marriage of Ernie and Ducky was the final drop in her cup of suffering and hesitations. She decided to talk to Aunt Michen; this was also Ernie’s advice. As he was leaving, he whispered to me that there was hope of a happy outcome. I have to say here that during the whole of those three days I suffered terribly anxiety; all the relatives kept asking me in confidence about her and, expressing their sympathy in the most touching way, wished me all the best. But all this provoked in me even greater fears and doubts that perhaps things would not be resolved.

The Emperor [Wilhelm] also tried, he even had a talk with Alix and on that morning of 8th April brought her to us at home. She then went to Aunt Michen and soon afterwards came into the room where I was sitting with the Uncles, Aunt Ella and Wilhelm.

They left us alone and… the first thing she said was… that she agreed! Oh God, what happened to me then! I started to cry like a child, and so did she, only expression immediately changed: her face brightened and took on an aura of peace. No! I cannot tell you how happy I am and yet how sad that I am not with you and that I cannot embrace you and dear Papa at this moment. My whole world has been transformed, and everything, nature, people, places, all seem attractive, good and full of joy. I simply was not able to write, my hands were trembling and from then on, in fact, I did not have a single moment free." - Nicholas in a letter to his mother, written April 10/22, 1894

Above: Alix with her father, year 1889.

Above: Alix getting ready for her first ball with Ella, year 1889. This ball marked Alix's "coming out" into society, when she was now considered a marriageable young woman and wore her hair up for the first time.

Above: Alix, year 1889.

Above: Alix with her sister Elisabeth "Ella", year 1889.

Above: Alix, year 1892. Photo courtesy of Tatiana Z on Flickr.

Above: The Hesse sisters, year 1894.

Above: Alix with Princess Helena Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, Gretchen von Fabrice, and a Fräulein Schneider, year 1894.

Above: Nicholas' parents, Tsar Alexander III (1845-1894) and Empress Marie Feodorovna (1847-1928), formerly Princess Dagmar of Denmark, year 1893.

Above: Alix at her writing desk, early 1890s.

Above: Alix in a portrait painted by Friedrich August von Kaulbach, early 1890s.

Above: Nicholas, year 1893.

Above: Alix, year 1894.

Above: Nicholas and Alix on the day of their engagement, year 1894.

Above: Nicholas and Alix in an official engagement photo, year 1894.

Despite Alix's young age, her health was never robust. As a little girl, she had fallen through a glass pane while playing that badly scratched her legs and gave her sciatica, plaguing her for the rest of her life with pains in her "wretched legs" that were so severe that they often put her in beds, chaises, sofas and wheelchairs. She also suffered from terrible migraine headaches, along with ear inflammation and poor circulation, and she was recommended to go on bedrest, trips to take the waters, and rest cures to help her with her leg pains. While at Harrogate in May 1894 on one of these trips, Alix's extreme shyness made her feel overwhelmed, embarrassed and tormented by all the people gathering to catch a glimpse of her, a princess AND one of Queen Victoria's granddaughters, as she went through town in a bathchair to the Victoria Bathing House to receive sulphur baths and peat baths. What she saw as an "unpleasant" intrusion, she tried her hardest to dull with avoidance, such as using the back entrance of the Prospect Place villa, Cathcart House, that she was staying at.

"The people are obvious here, now that they have found me out. They stand in a mass to see me drive out and tho' I now get in at the backyard, they watch the door and then stream to see me and some follow too. One obvious woman, who comes quite close too, and stares ... Then when I go into a shop to buy flowers, girls stand and stare in at the window. The Chemist told Madelaine that he had sent in a petition that a policeman should stand near the house to keep people off, as he saw how they stared. Most kind, but it makes no difference. 'That's her', one said behind me. If I were not in the bathchair I should not mind. When Gretchen was in a shop this morning, a little girl came in and the man asked her whether she had seen me. She said yes only once as I had my carriage in the courtyard, as I did not seem to like being looked at. I wish the others would remark it too and keep away and not stare with opera glasses through their windows. It is too unpleasant!" - excerpt of a letter from Alix to Nicholas, written May 16, 1894 at Harrogate.

Above: Cathcart House, where Alix stayed during her time in Harrogate in May 1894. Photo courtesy of Betty Longbottom via Wikimedia Commons.

It was also during this time that Alix discovered that her hostess, a Mrs. Allen, had just had twins. Alix loved babies, and when she went to visit them, her shyness melted away; she was very lively, chatty, generous and informal, asking the Allens to treat her like an ordinary person. She was in her element. Alix became the twins' godmother, as she had requested, and the two babies were named Nicholas and Alix, in honour of herself and her future husband.

Above: Cufflinks given to Nicholas Allen by Alexandra in 1910.

In June 1894, Nicky came to visit England and was again reunited with Alix. They spent three beautiful days together staying with Alix's sister Victoria Mountbatten and her husband, Prince Louis of Battenberg, at their rented house by the River Thames at Walton, enjoying each other's company: the enamoured young couple went on walks, sat on a rug underneath a chestnut tree while he read aloud and she sewed, and went on carriage drives, with Nicky being unchaperoned for the first time. It was complete bliss for them, and for a long time afterward, just the mere mention of Walton was enough to bring tears to Alix's eyes.

Above: Nicholas and Alix, year 1894.

Above: Victoria and Louis.

Above: The house Victoria and her husband rented at Walton-on-Thames. Today it functions as a Montessori preschool. Photo taken by Nigel Cox.

The wedding of Nicholas and Alix was scheduled for 1895, but an unexpected and major event pushed it back: Nicholas' father, Tsar Alexander III, had fallen ill with kidney disease, and his condition was so grave that he was not expected to live much longer. By now, he had accepted that Nicholas intended to marry Alix, and he wanted to see her before his death, so Alix and her friend, Gretchen von Fabrice, immediately made the journey by train to the Crimea, and at Livadia Palace, Nicholas and Alix were betrothed in front of Alexander, who died on October 20 (Old Style date)*. The next day, Alix made her conversion and was formally accepted into the Russian Orthodox Church, and she took a new name: Alexandra Feodorovna. She was now the Empress and Nicholas was, of course, now Tsar Nicholas II (although their coronation would not take place until 1896). The people saw Alexandra's becoming Empress so soon after her father-in-law's death as a bad omen, and they whispered: "She comes to us behind a coffin. She brings misfortune with her."

"How I wish you dear ones were here, as I miss you horribly. But it is a great comfort being with my beloved Nicky so as to help him whenever he needs it. — I have only once seen his dear Father, because not to excite him too much, latterly he slept & eat a little better but his legs are so swollen & his body itches so." - written by Alix in a letter to Ernst, dated October 13/25, 1894

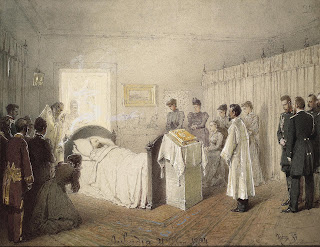

Above: Alexander III on his deathbed receiving the last rites. Drawn by M. Zichy, year 1895.

Although the court was in mourning, the imperial couple were to be wed soon. Nicholas and Alexandra wanted to have the wedding at Livadia, but protocol demanded that there be a grand, formal ceremony in the capital, so, on November 26 (N.S.), 1894, they were married in the chapel of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. After the wedding, they stayed at the Anichkov Palace before going to stay at the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo, which, in time, would come to be their permanent home until 1917 (they moved there after the events of Bloody Sunday in 1905). The marriage was outwardly serene and proper, but in private it was characterised by intensely passionate physical love.

Above: Nicholas and Alexandra at their wedding, painted by W.H. Grove after Lauritz Tuxen, year 1894.

Above: Nicholas and Alexandra just married, leaving the chapel. Photo courtesy of humus on Livejournal.

"Am inexpressibly happy with Alix. It is a shame my duties take up so much time, which I would prefer to spend exclusively with her." - Nicholas in his diary, written November 17, 1894

"

Never did I believe there could be such utter happiness in the world -- such a feeling of unity between two mortal beings. No more separations. At last united, bound for life, and when this life is ended we meet again in the other world and remain together for Eternity." - The newly wed Alexandra, written in Nicholas' diary, November 26, 1894

"Our wedding seemed to me a mere continuation of the funeral liturgy for the dead Tsar, with one difference: I wore a white dress instead of a black one." - Alexandra in a letter to one of her sisters

"The bridegroom-Tsar arrived a little before the Empress and the bride. He was wearing the uniform of the Hussars of the Life Guard. ... I presented the bride with a bouquet of white roses with red velvet ribbons, embroidered in gold with the cipher of Peter I. ... The Emperor is just a little shorter than his bride, but not so much as to be noticeable. They both stood motionless under the crowns. I was able to see their faces as they circled round the lectern: their eyes were lowered, their expression concentrated. And then for the first time after the Emperor we heard the name of his bride: the Devout Tsarina and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna." - from the diary of Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich (KR), written November 27, 1894

"You cannot think how intensely happy we feel here all alone. Only for luncheon we see the Lady & Gentleman, else we are quite to ourselves — and that joy is greater than I can say. The sweet Boy is writing & reading through his papers & I am sitting at my dressing table writing & eating an apple. ... I can't yet believe I am married. If you only knew how intensely happy I am, & I never can thank God enough for giving me such a treasure for a husband." - written by Alexandra in a letter to Ernst, dated November 23/December 5, 1894

"Yes, my dear old boy, you are right in saying that I have got the greatest treasure in this world by having 'our Sunny' as my own little adored wife! I need not tell you what my feelings are — it would be useless trying to do so as words & expressions are too poor and then you may judge better than any one what a sweet loving gentle angel she is! I have never been as happy in my whole life as during these five days we have spent here all alone, hand in hand & heart to heart. ...

... While I am writing to you Sunny is lying on a sofa reading a book & perpetually asking me whether I have finished this scribble? Please forgive me, dear Ernie, if I have put in rubbish, as I have to hasten so as to obey my wife. Do you know, I can hardly get over it yet, to think that I am married seems so wonderful & so delightful that it is difficult to believe it yet." - written by Nicholas in a letter to Ernst, dated November 26/December 8, 1894

Although Alexandra was blissfully happy in her marriage to Nicholas, she found Russian court life difficult to bear. When she arrived in Russia, she knew nothing of its customs and superstitions, and she had not yet learned much Russian, although, contrary to what has been accepted as fact for more than 100 years, with time she became proficient in the language. The Imperial Russian court was extremely formal, with all its rituals and rigid rules. Even being a granddaughter of Queen Victoria could not have prepared Alexandra for this, and she felt completely overwhelmed and lost. What made her feel worse was that her mother-in-law, the Dowager Empress, had set her an example to live up to: an Empress of Russia had to be publicly visible, sociable, open, warm and lively. This had made Marie Feodorovna very popular and well-liked as Empress, but Alexandra did not have the sociable, outgoing personality that she did, and Marie was frustrated with her daughter-in-law for not living up to her example of what a Russian Empress should be like. Then there was the criticisms Alexandra received: she was very shy and introverted, her few friends themselves were never popular, she could never dress right, and she was horrible at speaking French, which was the official language of the Russian court. Another reason why she was not liked was because of her German birth, and there was strong anti-German sentiment at the Russian court. She had no liking for the court society, the people of which she found "frivolous" and "ill-natured", and she was determined to avoid it. Alexandra was very unpopular at court, and her shyness and aloofness were seen as haughtiness and pride. She never made any effort to change this and make herself likeable, which only contributed to her unpopularity.

"At the same time as she was attempting to support her husband in his unaccustomed role as Russia's autocrat, Alix was also having to adapt herself to the enormous changes that had taken place in her own life. It helped her greatly that her marriage was, and always remained, very happy. For any young woman, however, the first months of married life can be difficult and few would relish a wedding which occurred one week after their father-in-law's funeral. In Petersburg Alix knew no one. Even her sister Elizabeth, whose husband was Governor-General of Moscow, was seldom in the imperial capital. Nicholas himself was overwhelmed with work and saw little of his wife in the daytime. In the family circle Alix could speak her native English. But outside it, in Petersburg society, Russian or French was necessary. The young Empress had only just begun to learn the former. She was never very happy speaking the latter, which tended to desert her in moments of stress. In the first months of her marriage such moments were plentiful, for as Empress she was forced to be on perpetual show." - from

Nicholas II, by Dominic Lieven

"The Petersburg aristocracy never liked the young Empress and by 1914 had come to hate her with quite extreme venom. Neither Darmstadt nor Queen Victoria were much of a preparation for Petersburg, whose extravagant luxury and low morals shocked Alix. This was a world in which the following conversation could be overheard between two ultra-aristocratic youths: 'Baryatinsky said to Dolgorukov that he is the son of Peter Shuvalov, to which Dolgorukov very calmly answered that by his calculations he is the son of Werder [the former Prussian Minister.]' If Alix had been exposed to the world of her uncle the Prince of Wales's Marlborough House set rather than that of his widowed mother, Queen Victoria, all of this might have come as less of a shock." - from

Nicholas II, by Dominic Lieven

"The young Empress was ill-equipped by temperament to win this society's loyalty. She danced badly, was extremely shy and loathed large gatherings of strangers, at which she became stiff, cold and silent. Prince Serge Volkonsky, who as Director of the Imperial Theatres met Alix frequently in the 1890s, commented that she 'was not affable; sociability was not in her nature. Besides, she was painfully shy. She could only squeeze a word out with difficulty, and her face became suffused with red blotches. This characteristic added to her natural indisposition towards the race of man, and her wholesale mistrust of people, deprived her of the slightest popularity. She was only a name, a walking picture. In her intercourse with others, she seemed only to be performing official duties; she never emitted a congenial spark.'" - from

Nicholas II, by Dominic Lieven

"The Empress was herself nursing her little daughter, much to the indignation of her relatives, who considered that it was not a befitting thing to do in her position, and she liked to retire early. At all these receptions she was lovely in appearance, and was gorgeously dressed, perhaps too gorgeously, and she certainly made a splendid apparition when she entered a ballroom. But people thought her dull, and found her devoid of that kind of conversation which goes by the name of 'small talk'. She was far too frank to hide her feelings, and could not bring herself to show herself amused whilst in reality she felt bored. This was noticed, and of course resented. People expect one to be interested in their doings and sayings, and an Empress who hardly ever smiled did not tally with their estimate of what she ought to have been. ... Alexandra Feodorovna was fast becoming unpopular, simply because she would not lower herself to the level of those who criticised her so openly and so persistently." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"Already in those early days there existed a party against her, which never missed an opportunity to compare her with her mother-in-law, and this not to her advantage. The Dowager had been immensely liked, partly because she had always made it a point to appear to like every one she knew or met. She had not perhaps been more talkative than her daughter-in-law, but she had smiled sweetly and nodded kindly to all her acquaintances, and she had never noticed the shortcomings of her neighbour. Alexandra Feodorovna, on the contrary, was inclined to be satirical, and had a keen sense of humour, that was not destined to add to the pleasures of her existence." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"The Empress was accused of not being true to class, but on one point she was inflexible; she allowed no interference with her friendships. I sometimes wondered why she preferred 'homely' friends to the more brilliant variety — I ventured to ask her this question, and she told me that she was, as I knew, painfully shy, and that strangers were almost repellent to her.

'I don't mind whether a person is rich or poor. Once my friend, always my friend.'

Yes, her loyalty was indeed worthy of the name of a friend, but she put friendship and its claims before material considerations. As a woman she was right, as an Empress perhaps she was wrong.

The aristocracy never tried to understand the real Tsaritsa. Their pride was up in arms against her — she found no favour in their eyes." - from

The Real Tsaritsa (1922), written by Lili Dehn

"Many times I wished to warn my mistress of the criticisms to which she willingly lent herself by her manners and conduct, but I never dared." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"Of course a woman with a little experience of the world might have known how to conciliate the different elements with which she was brought in contact. But Alexandra was not a diplomat, and, moreover, never could hide her feelings. She thus contrived to wound those whom, perhaps, in her secret heart she was most anxious to please." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"When she was compelled to appear at a ball or State function, she did so with such a bored look that it could not fail to be noticed and of course was resented." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"... Opposition of any kind had the effect of exasperating her and of driving her to do precisely what she ought not to have done. She had the idea that as the wife of an autocratic ruler she was placed above every kind of criticism, and that no one dared to make any remark concerning her conduct or manners. Of course this was a mistaken idea, but it had so thoroughly taken hold of her mind that nothing could ever drive it away, and it has certainly contributed to the misfortunes which have assailed her later on." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"At the time of her marriage St. Petersburg society was well disposed toward my unfortunate mistress, and it would have been easier for her to have made herself popular. Unfortunately she had ... a sarcastic tongue, and made no secret of her likes and dislikes; nor did she hesitate to ridicule certain customs to which old and important dowagers clung with persistency. She always feared to be thought too familiar, owing to the fact that the Imperial family, from the very first day of her arrival in Russia, had drilled into her ears the caution that St. Petersburg was not Darmstadt, and that the free and easy manners of a little German town would be out of place at the Court of the mighty Czar of All the Russias. She had therefore fallen into the other extreme, and disciplined herself to be as stiff as possible." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"On the New Year ..., St. Petersburg ladies made up their minds not to put in an appearance at the great reception which followed upon divine service in the Winter Palace, a reception during which Court society offered its New Year's wishes to the sovereigns. So about four of them, who by virtue of the official position of their husbands could not absent themselves, were the only ones who attended the function. This absence, en masse, could not but be noticed, and of course the Czarina was offended. But she was powerless to retort otherwise than passively, which she did by avoiding in the future showing herself in public, also by discontinuing her audiences and even the ball which had been considered as in indispensable feature of every winter season in the Russian capital." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"I remember that one day whilst we were discussing the question of what kind of new clothes she would want for the coming winter, I remarked that she ought to order more evening dresses than she had done. The Empress interrupted me with the remark that she did not mean to have any more, because there would be no necessity for her to have them. I observed then that it would be a great disappointment to many of the young girls about to make their appearance in society for the first time if no Court balls were given. Alexandra Feodorovna got quite angry, and, getting up with impatience, exclaimed, 'I cannot understand why it is expected of me to amuse all the silly children their parents are bringing out.' Happily for her no one was present when she gave way to this fit of temper, but one may imagine how it would have been commented upon by any of her numerous enemies had they chanced to overhear it." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"My mistress would not hear reason, and at last declared that it was useless to be an Empress of Russia if one could not do what one liked, and that all she craved was the privilege to be left alone and allowed to enjoy, unrestrained, her taste for solitude. In that respect the Empress was certainly not quite normal, and at times she most undoubtedly suffered from what is called the mania of persecution. People abroad have attributed this abnormal condition of hers to the dread of revolution, the spectre of which was supposed to haunt her constantly. This, however, was not at all the case, because long before any one had an idea that revolution might break out, my mistress was already affected by that strange fear of seeing strangers approach her. The fact is that she had become morbid, thanks to the latent dislike which she knew but too well was felt in regard to her, and which worried her to the extent that she felt disgusted with the world in general and had come to the conclusion that it was not worth while to try to conciliate it, but that the best thing to do was to avoid seeing too much of it." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"... She was too frank, too honest, too true, to be able to play a comedy, and diplomacy was an art utterly unknown to her. She had not been trained in dissimulation, and she despised this atmosphere of the Court where a curb on one's thoughts and words was indispensable. In certain respects she was a child, with a child's impulsiveness and beautiful indifference to the judgements and appreciations of the world, and this innocence of her mind and heart made her no match against the intrigues that surrounded her." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

Alexandra's social ineptitude also did not go unnoticed by foreign visitors and hosts:

"... The Empress ... did not seem to care for the elaborate programme of festivities which had been planned in her honour, and showed herself more than usually listless and indifferent. She was tired, and besides felt embarrassed at what she considered to be exaggerated expressions of admiration with which she was greeted." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"The Russian Ambassador, Baron Mohrenheim, gave a luncheon party at the Embassy to which he invited the leaders of that part of French society called the Faubourg St. Germain. Among those who responded to his appeal were the Duchesses de Luynes and d'Uses, the Countess Aimery de la Rouchefoucauld, and the Duchesse de Doudesuville. The Czarina had been told that these ladies were not in favour in Republican circles, and she felt afraid to show them any attention which might be interpreted as a desire to please the enemies of the Régime which was welcoming her. She consequently allowed them to be presented to her, but spoke but a few words to them, and showed herself so cool in regard to them that of course she gave grave offence, and Baron Mohrenheim was told that his 'Impératrice n'était pas aimable'." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

Marie Feodorovna also had other reasons to be frustrated with her daughter-in-law, whose tastes and "imprudent" openness about her opinions were making her even more disliked in society:

"One incident in particular had aroused the ire of the Empress Dowager, who had made no secret of her indignation against her young daughter-in-law on the subject. The Czar and his wife had accepted an invitation to dine and spend the evening at the barracks of the Hussar regiment, of which the Emperor, when heir to the throne, had been in command. Nicholas II. was enjoying himself, as he invariably did when amidst his old comrades of former times, but the Empress was far from doing so, therefore, when eleven o'clock struck, she determined she had had quite enough of it, and, calling to her husband, said loudly and distinctly in English: 'Now come, my boy, it is time to go to bed!' One may imagine the horror of the assistants on hearing the autocrat of All the Russias addressed in public as 'my boy' by his imprudent wife. The incident was widely commented upon and discussed, and Marie Feodorovna thought it her duty to remonstrate with her daughter-in-law on the subject, saying that she had never ventured to address Alexander III. in presence of others, let alone in an official occasion such as this one had been, otherwise then as 'Sir' or 'Your Majesty.' My mistress took these remonstrances in very bad part, and the relations between the two ladies did not improve after this affair." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"The Empress Marie had been in the habit of receiving in her own private boudoir the ladies who craved an audience from her, and of asking them to sit beside her. Her daughter-in-law made it a point to give her audience standing, and to converse for a few minutes without ever offering a chair to the old women who had applied for the honour of an introduction to her. She coldly extended to them her hand to kiss, which further incensed them, and her natural shyness, added to this stiff reception, of course made her many enemies. She began to be criticised, and that in no friendly spirit. Unfortunately she became aware of this, and it set her from the very first against the people she ought to have tried to make her friends." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"Then, again, the Czarina had the imprudence to express in public her disgust at what she called the loose manners of St. Petersburg society. She tried to become acquainted with all the gossip going about town, and declared that she was going to reform the morals of her empire, proceeding by striking off the list of invitations for a Court ball the names of all the women supposed rightly or wrongly to have had a flirtation of some kind. The result was that hardly any ladies appeared at this particular ball, with the exception of mothers with girls to bring out, and the whole of St. Petersburg rose up in arms against its Empress. It was decided to boycott her, which was done, and the Empress Mother was asked to interfere and to explain to her daughter-in-law that it was not her business to brand with any kind of stigma the names of ladies in regard to whom no open scandal had ever taken place." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"Just like Queen Alexandra after Edward VII's death, the Empress Marie stressed her precedence over her son's wife in court ceremonies and hung on to many of the crown jewels, most of which should have gone to her daughter-in-law. Though the two empresses always remained on relatively polite terms they could scarcely have been more different. Alix was much more serious and intelligent but she sadly lacked her mother-in-law's vivacity or her social skills. Living under her mother-in-law's roof, she quickly became aware of the many unfavourable comparisons being drawn between her and Marie in Petersburg society." - from

Nicholas II, by Dominic Lieven

"Quite unlike her mother-in-law, who was an expert in smoothing over awkward moments by her warmth and tact, Alix's combination of shyness and obstinacy made her extremely rigid. Even in trivial matters she seemed unwilling or unable to adapt herself to Petersburg society and its ways. Volkonsky recalled that when Nicholas II came to the theatre or ballet alone, he would chatter away amiably. 'But I must add, this was only when he was alone — without the Empress. Alexandra Feodorovna evidently acted as a restraining influence on her husband. She was cold and composed. Her entrances and her exits were in pantomime. She never made an observation or uttered an opinion, or asked a question.'" - from

Nicholas II, by Dominic Lieven

Above: The Anichkov Palace, residence of Marie Feodorovna. Photo courtesy of A. Savin via Wikimedia Commons.

Above: The Alexander Palace, the favourite residence of Nicholas and Alexandra. It would be their permanent home until their exile in 1917. Photo courtesy of Flying Russian via Wikimedia Commons.

Above: Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna, formerly Princess Dagmar of Denmark, painted by Ivan Kramskoi, 1880s.

Above: Alexandra in a portrait painted by Heinrich von Angeli, year 1896 or 1897.

Above: Alexandra. Photo courtesy of Ilya Grigoryev on Flickr.

Another expectation of an Empress of Russia was that she give the country an heir to the throne. The Salic Law put in place by Tsar Paul, who resented his mother, Empress Catherine the Great, ensured that only male heirs would be valid, and there could never be any female heir to the throne except in the unlikely case that there be no eligible male relatives left alive. Therefore, the heir to the Russian throne had to be male, and there was enormous pressure on Alexandra to produce a boy who would grow up to be the next Tsar. In 1895, Alexandra became pregnant with her first child, whose arrival she awaited impatiently, and on November 3/15 of that year, the baby was born: a daughter, whom they named Olga. Everyone was very happy for Nicholas and Alexandra, although they were disappointed that the child was not a boy. The imperial couple were overjoyed at being parents, and it did not matter to them that Olga was a girl. They insisted on taking care of her mostly themselves, and Alexandra often wrote about the new baby and her care in letters.

"What a joy it must be to have a sweet little wee child of one's own. — I am longing for the moment when God will give us ours — it will be such a happiness for my darling Nicky too, & he has so many sorrows & worries that the appearance of a tiny Baby of his very own will cheer him up." - written by Alexandra in a letter to Ernst, dated July 5/17, 1895

"I had one day a slight chill in the stomach, & after that got such pain, especially with strong Wehen — as it has gone down very low. This is the third day I am lying in bed or on the sopha, as must keep very quiet. Güntz slept here these last nights, — I have seen the Dr too, & all leads to think it may make its appearance any day, & that would not be too early, according to position & feeling, tho' we all expected end of October, or 4th of November. All is going well, & one need not be anxious, only I may not get up till those pains have stopped, as they have nothing to do with the whole." - written by Alexandra in a letter to Ernst, dated September 28/October 10, 1895

"I am better, since I last wrote, but must still keep quiet. I long for Baby to come, the wait [weight] & movement are so very strong." - written by Alexandra in a letter to Ernst, dated October 2/14, 1895

"Baby won't come — it is at the door but has not yet wished to appear & I do so terribly long for it." - written by Alexandra in a letter to Ernst, dated October 9/21, 1895

"How happy you must be to have yr Baby [Elisabeth] again — she no doubt looks like a giantess after our little One. She is such a pet. She slept in our bedroom the other night, & yesterday, as poor Günst was layed up for two days. ... Orchie slept in the blue room & scarcely spoke to me, so offended we did not have Baby with her. But Tiny was too sweet. When she cried I walked about with her & changed her or rang for the wetnurse, but she was good & slept for some hours. I wash her every evening in her bath & then dress & sew her up, an intense happiness." - written by Alexandra in a letter to Ernst, dated December 12/24, 1895

"It is a radiantly happy mother who is writing to you. You can imagine our intense happiness now that we have such a precious little being of our own to care for and look after." - from a letter from Alexandra to her sister Victoria, written December 13, 1895.

"Baby is flourishing, thank God — grows in length & breadth — her length is 62½ cm., 55½ when she was born 2 months ago.

I am not at all enchanted with the nurse — she is good & kind with Baby, but as a woman most apathetic, & that disturbs me sorely. Her manners are neither very nice, & she will mimic people in speaking about them, an odious habit, wh. would be awful for a Child to learn — most headstrong, (but I am too, thank goodness). I foresee no end of troubles, & only wish I had an other." - written by Alexandra in a letter to Ernst, dated January 9/21, 1896

"The dear, merry little thing is such a comfort to one, when one feels sad & depressed. ...

Baby begins taking other food besides now 3 times a day & has a salt bath every morning according to my wish, as I want her to be as strong as possible having to carry such a plump little body." - written by Alexandra in a letter to Ernst, dated July 12/24, 1896

"Baby is growing and tries to chatter, the beautiful air gives her nice pink cheeks. She is such a bright little Sunbeam, always merry & smiling." - written by Alexandra in a letter to Ernst, dated March 26/April 7, 1897

Above: Nicholas and Alexandra with their first daughter and eldest child, the Grand Duchess Olga, year 1896.

Above: Alexandra with Olga, year 1896.

Above: Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna, year 1898.

Above: Alexandra in her famous Mauve Room, year 1895.

Above: Alexandra in the Mauve Room.

"We take long walks, Baby sweet goes out too. It was sad to leave her so long to-day. — I have to begin to stop nursing her now on account of Moscow, & that is so sad as I enjoyed it so much. — I continue receiving people — the other day 35 ladies, & yesterday 23 gentlemen, it is enough to make one cracked." - written by Alexandra in a letter to Ernst, dated April 13/25, 1896

"The nearer the day of our meeting approaches, the happier I get, and yet the idea of all the festivities at Moscow frightens me terribly. It will be most tiring & often very shy work. — The entry will be most dull for me, as I shall drive all alone through the town." - written by Alexandra in a letter to Ernst, dated April 22/May 4, 1896

Nicholas and Alexandra were formally crowned on May 14/26, 1896 in an elaborate ceremony in Moscow. It was one of the first public events to be filmed. Despite the fact that she was the wife of the "Master of the Russian Land", the crowd made it clear to Alexandra that she was not exactly welcome.

"The unpopularity of the young Sovereign was already an established fact when the Coronation took place at Moscow. It appeared quite plainly on the day she made her public entry into the ancient city, when the crowds greeted her with absolute silence, whilst they vociferously cheered the Dowager Empress. Alexandra felt this deeply, and when she was alone in her rooms she wept profusely over this manifestation of the displeasure of the nation in regard to her person. It was the first time that I had seen her giving way to grief of any kind, and it affected me very much, especially in view of what was to follow." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

Four days later at Khodynka Field, souvenirs such as small foods and commemorative cups were being passed out to the crowd. Rumour quickly spread that there would not be enough of these gifts for everyone, and there was a human stampede that left 1,800 dead and about 1,300 injured. The Tsar and Tsarina were later informed of the tragedy, and by the time the news reached them, a festive ball had been scheduled for that night at the French Embassy. Nicholas thought it best to not attend, but his uncles believed that it would be worse to offend the French than to appear cold and uncaring toward the Russian people, so he and Alexandra ended up going to the ball anyway. The imperial couple visited the survivors in hospitals the next day.

Above: The coronation of Nicholas and Alexandra, painted by Lauritz Tuxen, year 1896.

Above: Nicholas crowning Alexandra as part of the ceremony.

Above: Alexandra and her mother-in-law being taken to Assumption Cathedral for the coronation ceremony. Photo courtesy of humus on Livejournal.

Above: The coronation procession. Photo courtesy of humus on Livejournal.

Above: Assumption Cathedral in Moscow, where Nicholas and Alexandra were crowned in 1896. Photo courtesy of Uwe Brodrecht via Wikimedia Commons.

Above: The interior of the cathedral. Photo courtesy of Uwe Brodrecht via Wikimedia Commons.

Above: A cup made to commemorate Nicholas and Alexandra's coronation. It is now known as the Khodynka Cup of Sorrows. Photo by unknown, via Wikimedia Commons.

Above: Alexandra at her coronation, painted by Konstantin Makovsky, year 1896.

Two of Alexandra's ladies-in-waiting, Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden and Marfa Mouchanow, wrote of Alexandra's reaction to the tragedy in their biographies of her, and Buxhoeveden also described the hospital visits:

"

The Empress had to control her tears, but it was with a face of utter misery that she attended the Marquis de Montebello's wonderful entertainment. She behaved like an automaton, and all her thoughts were with the dead and dying. When the Imperial couple visited the hospitals where the victims lay, the scenes which they saw rent the Empress's heart. She would have given up all festivities on the spot and have nursed the people with her own hands, but official duties had to be fulfilled. Private feelings were held of no account. ...

The Empress never forgot her feelings at a State luncheon given just after their return from a hospital, at which she had surreptitiously to wipe her eyes with her napkin, as she remembered the terrible things she had seen." - from

The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna (1928), written by Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden

"

The young Empress, who had heard from one of her ladies the truth as to what had taken place, was most unhappy at the necessity of appearing in public on the day when such a terrible calamity had overtaken so many people, but she felt afraid to say what she thought, out of dread that one might think she had seized hold of the first pretext she could find in order to avoid showing herself at the Montebellos. It was already at that time suspected that her sympathies were with the Germans, and she was quite aware of the opinion concerning them and herself. She did not wish to give any further ground to this belief and thus did not follow the instincts of her heart ... So with sorrow in her soul, and anxiety in her mind, she went to that fatal ball and danced the whole night, though her thoughts were absent from the gay scene of which she was such an unwilling participator.

On her return to the Kremlin she dropped into an easy-chair beside her bed and burst into loud sobs, not heeding my presence or that of her other maids. Not caring for them to witness this explosion of sorrow, I sent them away, and tried to comfort my mistress to the best of my ability, entreating her to control herself, and not to distress the Emperor with the sight of her grief. But Alexandra Feodorovna kept weeping until at last I induced her to repair to the nursery, where the sight of her little girl sleeping in her cot brought back her composure.

And this was the woman who was represented to be cold and unfeeling, and who was reproached for her utter indifference in presence of a catastrophe of unusual magnitude!" - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

Alexandra also felt deeply moved when it came to matters concerning children and their illnesses and care.

"She was herself such a devoted mother that she felt particular sympathy with other mothers' griefs. The illness or loss of a child made an immediate appeal to her, were it the child of a great lady or that of some humble person." - from

The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra (1928), written by Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden

Alexandra clearly had a deep interest in and sympathy for human suffering, and this tied in with her deep love of religion. Since her conversion to Russian Orthodoxy, she embraced the Church wholeheartedly with a level of devotion and religious fervour that amazed even other members and which has been said to be incomprehensible to non-Russian minds, and she would spend hours on her knees, deep in prayer. She was intensely interested in the rituals, dogma and beliefs of Russian Orthodoxy, collected writings by the church fathers in Russian and Church Slavonic, and she zealously collected icons of saints, placing candles in front of them and obsessively arranging and re-arranging her icons in a specific order in the belief that misfortune would strike her or her family if she were to get the order wrong. There was a grand total of 800 icons in Alexandra's bedroom. Her favourite religious author was the American Presbyterian minister James Russell Miller, and she often wrote down quotes from his works about the joys of married life and raising children in a loving, Christian environment. Alexandra would become transfixed during religious ceremonies, either with a stone face or with tears rolling down her cheeks. She was a fervent believer in faith healing and the redemptive effects of suffering. The Russian Orthodox Church has a strong belief in faith healing and the power of prayer, as does the then-recently begun Christian Science movement founded by Mary Baker Eddy, which Alexandra was also interested in, and she was always seeking out hermits, monks, healers, soothsayers — men of God. She was also interested in the occult and was a believer in the paranormal, which was just as popular then as it is today, and even participated in séances. She was mainly introduced to this by the Montenegrin princesses Militza and Anastasia, who were nicknamed "The Black Sisters" or "The Crows" because of their own interest in the occult. In addition to this, with her constantly pessimistic and anxious character, Alexandra was also superstitious to an extreme. Like her mother and grandmother before her, and fittingly for the Victorian and Edwardian eras, she had a fascination with death and the afterlife.

"From their mysterious homeland the Montenegrins brought an unshakable belief in the supernatural. Witches and sorcerers had always lived there, in the high mountains grown up in wild forest, and some people there could talk with the dead and predict the fates of the living. All this was new to the granddaughter of the skeptical Queen Victoria; this mysterious new world intrigued her. ...

It was Alix's nature: if she believed in something, then she believed with all her heart, without reservation." - from

The Last Tsar: The Life and Death of Nicholas II (1992), by Edvard Radzinsky

"Like her mother, Alix was a fervent Christian. She abandoned Protestantism only after a great struggle. ... When in Petersburg, the Empress used to go to the Kazan Cathedral, kneeling in the shadow of a pillar, unrecognized by anyone and attended by a single lady-in-waiting. For Alix life on earth was in the most literal sense a trial, in which human beings were tested to see whether they were worthy of heavenly bliss. The sufferings God inflicted on one were a test of one's faith and a punishment for one's wrongdoings. The Empress was a deeply serious person who came to have a great interest in Orthodox theology and religious literature. She loved discussing abstract, and especially religious, issues, and her later friendship with the Grand Duchesses Militza and Anastasia owed much to their knowledge of Persian, Indian and Chinese religion and philosophy. ...

As Empress, Alix held to an intensely emotional and mystical Orthodox faith. The superb ritual and singing of the Orthodox liturgy moved her deeply, as did her sense that through Orthodoxy she stood in spiritual brotherhood and communion with her husband's simplest subjects." - from

Nicholas II, by Dominic Lieven

"People have spoken at length of her tastes for occultism and spiritism, and said that she looked for consolation for imaginary woes to the practices of turning tables and other rubbish of the same kind. Unfortunately this was true to a certain extent, because it is a sad fact that the Empress liked to sit at tables for hours in the hope that they would begin turning, and she firmly believed that people could come back from the other world and manifest themselves to their friends." - from

My Empress (1918), written by Marfa Mouchanow

"On many occasions I was able to watch the Empress during the long services of the Orthodox Church, in which the congregation stands from beginning to end. She stood erect and motionless — 'like a taper', as a peasant who had seen her said. Her face was completely transfigured, and it was plain that for her the prayers were no mere formality." - from

At the Court of the Last Tsar (1935), by A.A. Mossolov

"She became more and more attached to the Russian Church, throwing herself into the practice of its religion with all the fervour of her nature."

"In the case of Alexandra Feodorovna, mysticism was combined with a blind clinging to anything that might save her child, easily understood by some Russian minds, in whom religion is curiously mixed with superstition. An English, German or French brain cannot quite understand her mentality, which was a mixture of Western mysticism and her newly-acquired, somewhat narrow Orthodoxy; and, like many converts, Alexandra Feodorovna surpassed even the usual Russian attitude to religion." - from

The Life and Tragedy of Alexandra Feodorovna (1928), written by Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden

"It may be argued that most converts are usually fanatics, but this was not so in her case. With that 'thoroughness' which I have mentioned as one of her chief characteristics, the Empress was now more Russian than most Russians, more Orthodox than the most Orthodox. She was intensely religious. Her love of God and her belief in His mercy came before her love of her husband and her children, and she found her greatest happiness in religion at a time when she was surrounded by the panoply of Imperial splendour. She was to derive consolation from her religion throughout the Via Dolorosa of the saddened years, and, if it is indeed true that she met death in the noisome cellar-room at Ekaterinburg, I am sure that the same ardent faith sustained her in that last moment of agony. She told me that she had hesitated to accept the Emperor's offer of marriage until she felt that her conscience would allow her to do so and she could say with truth: 'Thy country shall be my country, thy people my people, and thy God my God.'" - from

The Real Tsaritsa (1922), written by Lili Dehn

"On her marriage she embraced the Orthodox religion and practiced it with characteristic sincerity. But she had not her grandmother’s well-balanced mind and, as the years passed, she grew more and more mystical, swayed by superstition." - from

Memoirs, by Prince Christopher of Greece